| History

You are my witness: students visit Srebrenica

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the conclusion of the Bosnian War and the genocide in Srebrenica. To commemorate this, Cara Hall, Layla Harrison and David Morgan visited Bosnia and Herzegovina between 7 and 11 January 2025. They embarked on the trip as part of research for an exhibition and speech at Cheltenham’s Holocaust Memorial Day Act of Remembrance on 27 January 2025. In this post they talk about the war and their experiences of visiting Bosnia.

The Bosnian War (1992-1995) was part of the breakup of Yugoslavia which was prompted by Slovenia and Croatia’s declarations of independence in 1991. The war was fought between the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) led by commander Ratko Mladic and the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH). The conflict included a 1425-day siege of the capital city, Sarajevo, and a genocide in Srebrenica in July 1995. The war claimed around 101,000 lives.

Mladic, who oversaw both the genocide and siege, was arrested in Serbia in 2011 after 16 years on the run. He was sentenced by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in 2017 on 10 charges, including one of genocide, five of crimes against humanity and four for violations of the laws or customs of war. He is currently serving a life sentence in the Hague.

The Srebrenica Genocide

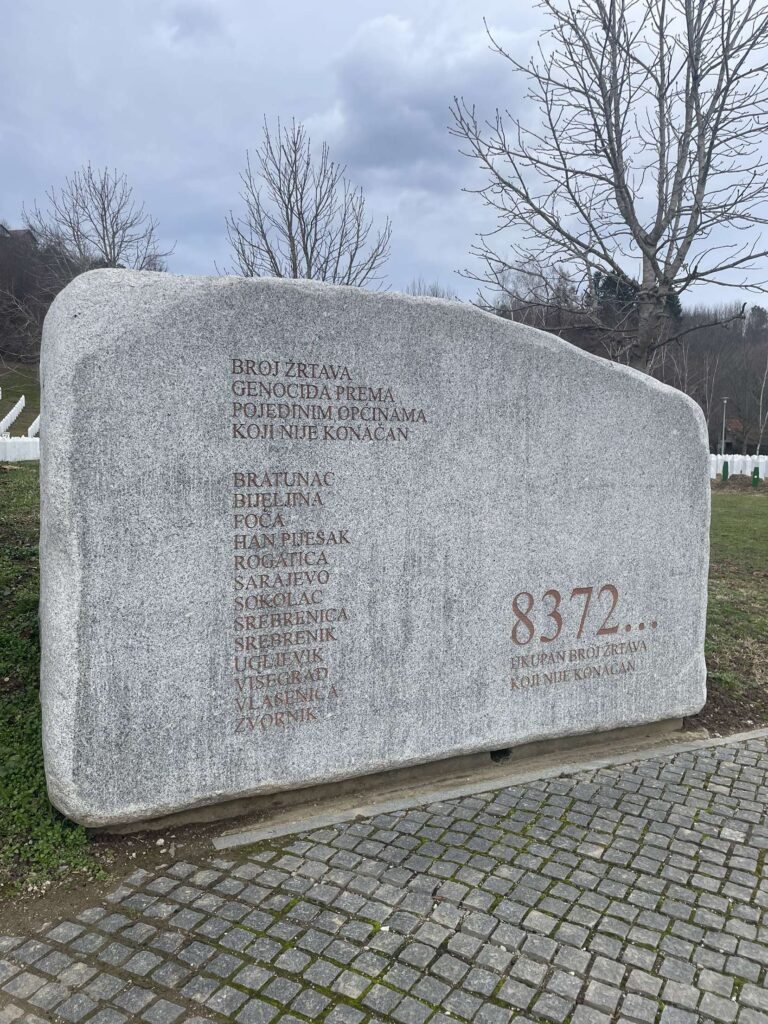

Between 11 and 22 July 1995, 8,372 Bosniak Muslim men and boys were systematically executed by the Army of the Republika Srpska. Before the killings, the enclave of Srebrenica was declared a United Nations ‘safe zone’ under the protection of Dutch Battalion forces, led by Thomas Karremans. This was to protect the Bosniaks from Mladic’s plans. However, the 370 Dutchbat troops were unable to keep the Serb advancements at bay, leading to the worst mass killing in Europe since the Second World War. The Dutch forces were based at a former battery factory in Potocari and the centre was used as a refuge for around 6,000 people fleeing from Srebrenica as the Serb forces closed in. However, an estimated 25,000 people were fleeing; this resulted in roughly 20,000 being forced to remain outside the compound.

As it became clear that the Dutchbat forces had become overwhelmed by the scale of the encroachment, around 15,000 men began the approximately 100km walk to reach the free territory of Tuzla. Many men were attacked along the route causing them to flee into the surrounding forest. However, Serb forces pretending to be UN peacekeepers using stolen weapons, coaxed the men out of hiding, rounding them up and executing them. Only 3000 men survived this march.

We were informed that to honour the victims many people hike across the same tough terrain each year, an event now known as the ‘Mars Mira,’ or the Peace March. Since 2007, the site of the UN base has been used as a museum with 25 rooms reflecting varying aspects of the genocide and wider political situation. Upon entry, we watched a 30-minute film which offered an overview of the war. This video was incredibly graphic and took us into the heart of the conflict, with images of death and executions shown without warning. The nature of this video was shocking, as in Britain videos of that kind are commonly censored. However, the graphic videos did remind us of the brutal nature of the killings.

After this, we toured the rooms containing large display panels that gave us a sense of what the victims endured during the conflict. One interesting aspect we discovered was the reflection the museum gave of the perpetrators. Despite repeated references to the sentence Mladic received in 2017 and his heinous crimes, the museum appeared to prominently highlight the more positive aspects of Mladic’s wartime role. Various images depicted him reassuring residents and handing out supplies to children, as well as talking to and negotiating with Karremans and the Dutch troops. These ideas offered a false image of Mladic’s role, an aspect we found particularly interesting but uncomfortable.

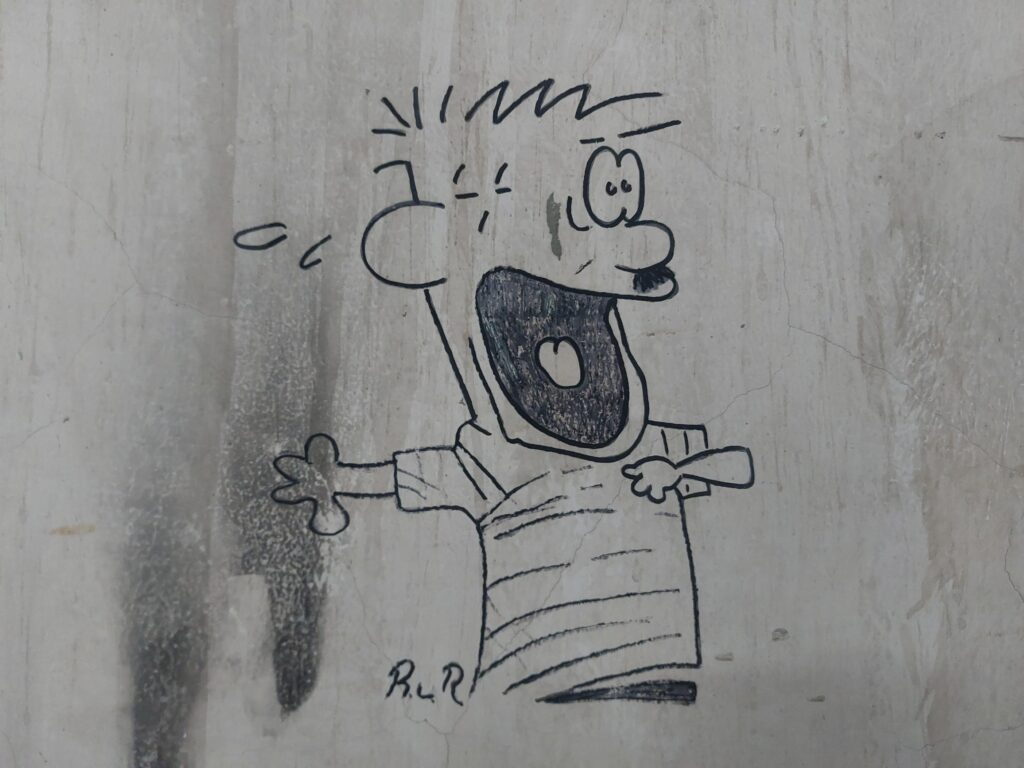

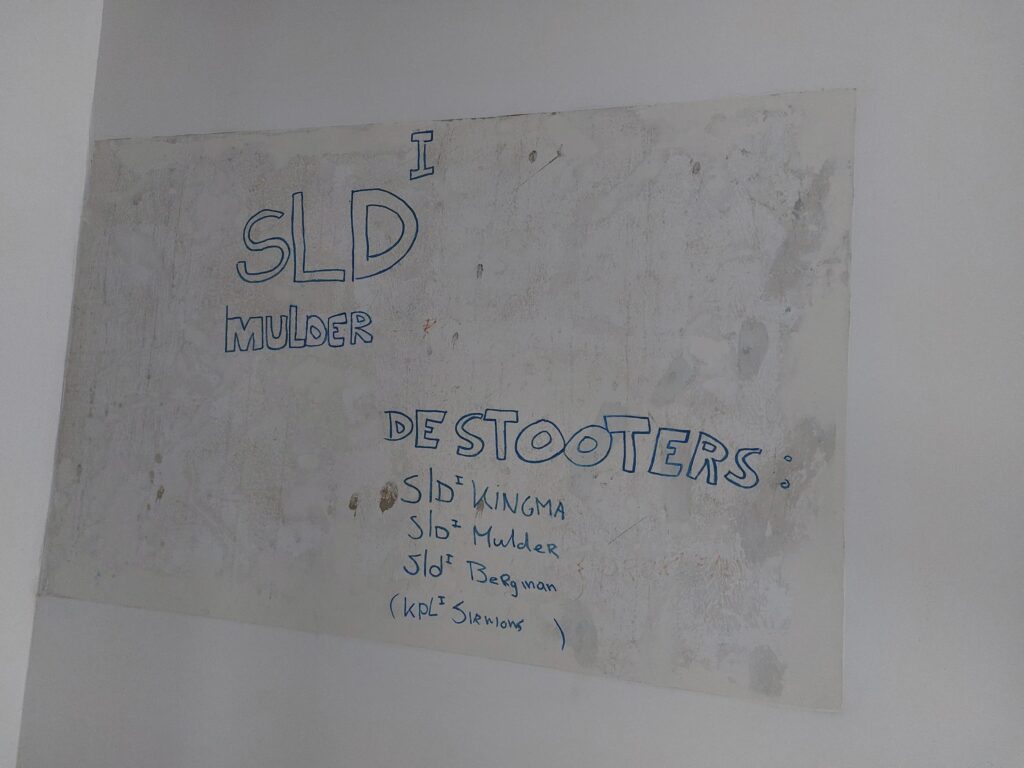

As we progressed through the museum, some of the graffiti left by the Dutchbat soldiers was still exposed, though much of it has since been covered. The exposed sections play an important role in highlighting the mental state of the UN forces whilst stationed there. Whilst some of the graffiti was factual and practical, including a tally of their time on the base, a large proportion of it has since been interpreted as derogatory.

Photographs of the graffiti in the Memorial Centre:

The museum offers an insightful commentary on the plight of the victims of the genocide, stories of mothers saying their final goodbyes littered most of the rooms. However, we discovered that despite it being mandatory for Bosnian children to visit the site, people living within the Republika Srpska, the semi-autonomous majority Bosnian Serb region agreed as part of the Dayton Peace Accords, do not visit the site and strongly opposed its original commission. This is due to their denial of the genocide and how the perpetrators, many of which are yet to be brought to justice, are celebrated and sheltered from authorities.

The Ghost Town

We also visited the ‘ghost town’ of Srebrenica, now inhabited by just 3000 people, down from 30,000 before the conflict. The town has just one school and a shop with most other institutions closing during and since the war. The scars of genocide are still present with many derelict buildings throughout the town. Whilst there, we saw the town’s only remaining mosque and witnessed remnants of how life used to be. One important factor we did note was the Christmas decorations that were present throughout the town, highlighting how the remaining residents are still trying to preserve a sense of normality and joy within their lives.

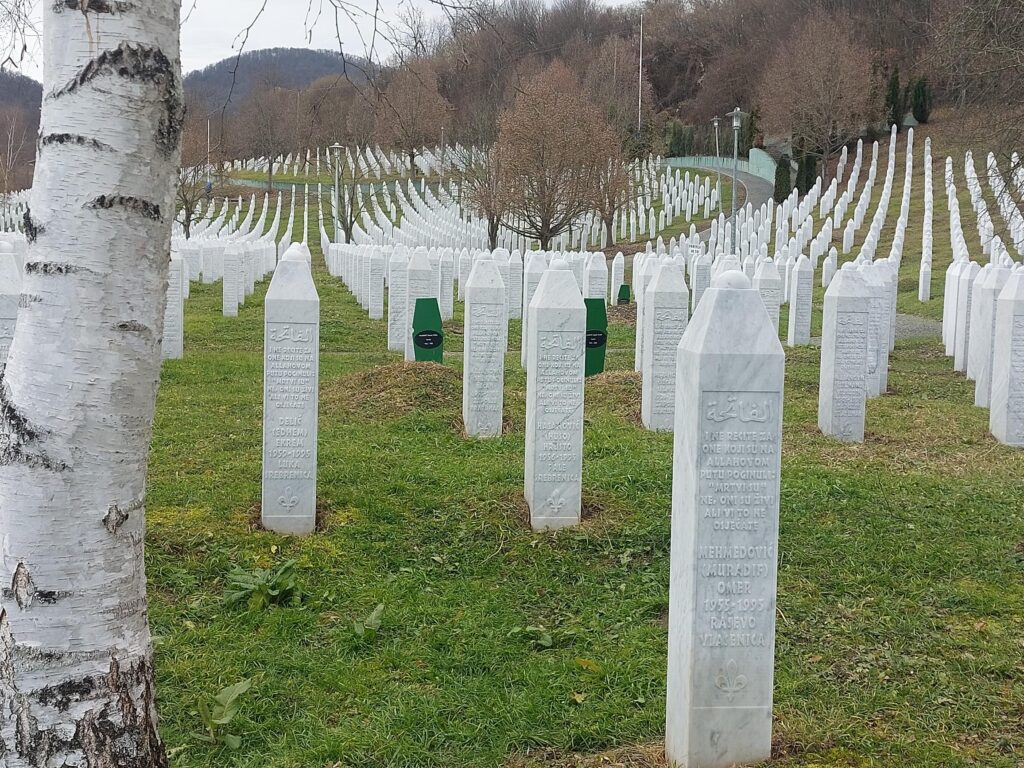

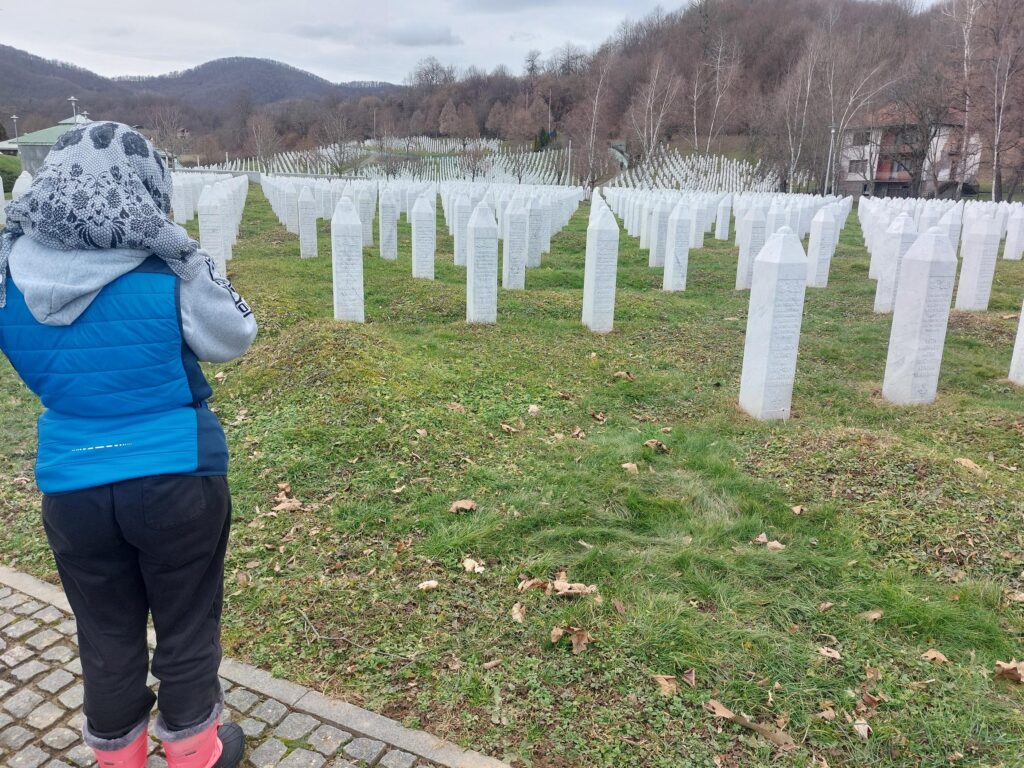

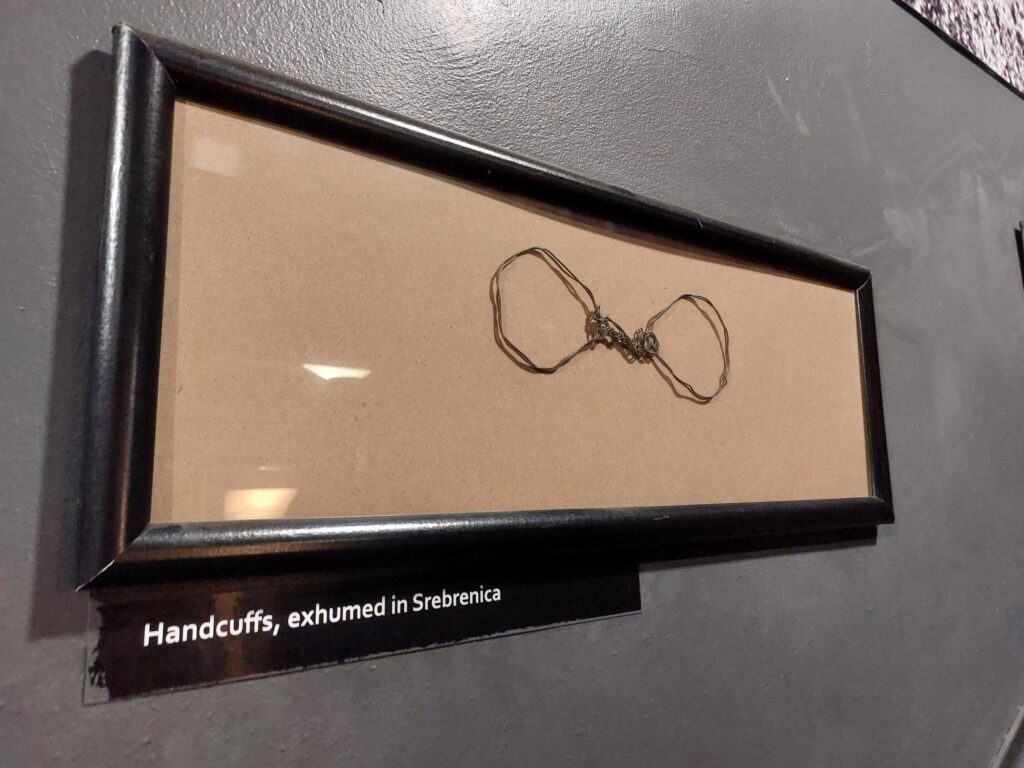

After visiting Srebrenica we returned to Potocari to visit the Memorial Cemetery. The site is opposite the memorial centre and received its first 600 victims in 2003. The cemetery is now the final resting place for the over 6000 innocent victims, whose bodies were discovered in mass graves throughout the region. Bodies were often discovered scattered between grave sites, sometimes 30 km apart, as they were exhumed and placed within secondary and tertiary graves in an attempt by the Serbs to conceal their crimes. Despite the high numbers already discovered, the number of victims continues to grow each year as more deposition sites are uncovered.

The site has been victim to a handful of attacks by the Bosnian Serbs, including bombs discovered hidden before the 10th-anniversary commemoration. However, these were safely disposed of without causing harm. There is now a constant police presence at the gate ensuring peaceful commemoration.

The trip for us was very insightful and helped us fully understand the nature of what occurred at the site, the scale of the cemetery gave us a first-hand account of the effect genocide can have on a region’s inhabitants and its landscape. Our guide was a 24-year-old Bosniak Muslim named Ibrahim. He had lived in Sarajevo most of his life and had been giving tours around Bosnia for around five years. To gain his perspective on the tours, we asked him how it felt to visit the memorial site regularly.

‘When I was here for the first time it was really hard, [the victims] are my people, the same ethnic group. While a lot of guides try to avoid giving the tour of Srebrenica. I look at it professionally. Someone needs to share the story, I like to share. When people show interest it makes me happy.’

We also asked him what children in schools in Bosnia were taught about the events of July 1995 and the wider war. Ibrahim outlined that within the Republika Srpska there is almost nothing. This is a consequence of the denial. Within the Bosnian federation, the other entity in the country, children at elementary school are not taught about genocide, and instead focus on only a small part of the conflict. It is interesting to understand that even in their own country little is taught about the worst mass killing on European soil since the Second World War.

Ibrahim also guided us through the Republika Srpska region. Whilst travelling through the mountains on the main road from Srebrenica, he pointed out a small warehouse where 1,000 men and boys were killed. The warehouse was hidden behind other buildings and existed without any visible commemoration of those who lost their lives, as proposals for this had been blocked by Serb officials. Without the tour guides, the awful history of this building will eventually be lost.

Coincidentally, the day we visited, 9 January, was the ‘day of Republika Srpska’, an annual celebration in the region. Despite the holiday being banned in 2015 and deemed unconstitutional, the day is still widely observed and as our guide said many celebrate the war and events surrounding it. Many houses hung the entity’s flag, which is similar to that of Serbia but lacks the distinctive crest. Ibrahim also described the entity as ‘puppets of [Vladimir] Putin’ due to the region’s alignment with Russia. This brought home to us that even though the conflict was 30 years ago tension is still rife within this region.

In 2004 the ITCY legally described the Srebrenica Massacre as a Genocide due to the systematic cleansing of Bosniak Muslim men and boys. Despite this, Some Serbs have claimed that the genocide was in response to Bosnian Serb civilian casualties inflicted by Bosniaks under the leadership of Naser Orić. These claims were rejected by the ICTY as an attempt to justify genocide. Many people in the Republika Srpska continue to deny the genocide occurred.

The Genocide’s effect on politics throughout Europe could be felt in the years following the war. After a 2002 report, the Dutch Government resigned from office citing its force’s inability to stop the massacre. Across three separate rulings, the Dutch state was found liable for the failings during the massacre leading to more than 300 deaths. Many Dutchbat soldiers have since regretted their role in the genocide, with the museums we visited containing stories from soldiers who’d committed suicide following the events.

For more information on the Genocide and to read the life stories of survivors, please visit:

Remembering Srebrenica – https://srebrenica.org.uk/

Holocaust Memorial Day Trust – https://hmd.org.uk/

Sarajevo

During our visit we stayed in Sarajevo, the location of a 1425-day siege, the longest siege of any capital city in history. The city has a rich and diverse history due to the Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian, socialist and western influences evident within the varied architecture. The old town, Baščaršija, is a maze of shops selling traditional copperware, foods and souvenirs around a square with the Sebilj, an ottoman-style wooden drinking fountain, in the middle. The more modern areas of the city with western and socialist influences are home to shopping centres and large department stores. In 1984, the city hosted the Winter Olympics, the first Slavic-speaking and Communist country to hold the Winter Games. Britain won just one gold medal during the games with Jane Torvill and Christopher Dean’s famous ‘Bolero’ routine becoming the highest-scoring figure skating performance of all time.

The city is also home to the site of the assassination of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The Archduke was assassinated on 28th June 1914 by teenager Gavrilo Princip as he travelled through the streets after visiting the city hall. The assassination is considered one of the most important events within the city as it led to the deterioration of international diplomatic relations ultimately leading to the beginning of the First World War. The site is directly opposite the Latin Bridge, a 16th-century structure with a rich history. Interestingly it was renamed ‘Princip’s Bridge’ in the Yugoslav era returning to its previous name in the mid-1990s .

The Siege of Sarajevo

Between 1992 and 1996 Sarajevo was under relentless attack by the VRS, an event which claimed the lives of 13,952 people, including roughly 1,600 children. We were lucky enough to briefly speak with a survivor, who was 8 when it began. He explained the way children often saw the shelling as a game, they would ‘celebrate’ not going to school, unaware of the grave reasons why the schools could not open. He also said that many people never left their homes during the siege but still were killed by shrapnel, whereas those who frequently left often were safe. This made many civilians believe that it was fate if they were killed, often allowing them to continue parts of their lives with relative normality. He also remembered seeing enemy encampments on the hillsides surrounding the city, with the site of the 1984 Winter Olympic bobsleigh track, a former enemy line littered with over 1000 land mines. The track today is a tourist attraction and is situated at the top of a cable car which allows you to see the city from above.

Since the conflict, concrete damaged when mortars fell has been filled with red resin and named the ‘Sarajevo roses’ due to their floral resemblance. There are many of them throughout the city in tribute to those who lost their lives there. The rose pictured is the site where 26 innocent people were killed as they queued for bread. This highlights how civilians died whilst posing no threat to the Serb enemy.

Srebrenica Genocide Memorial Exhibition

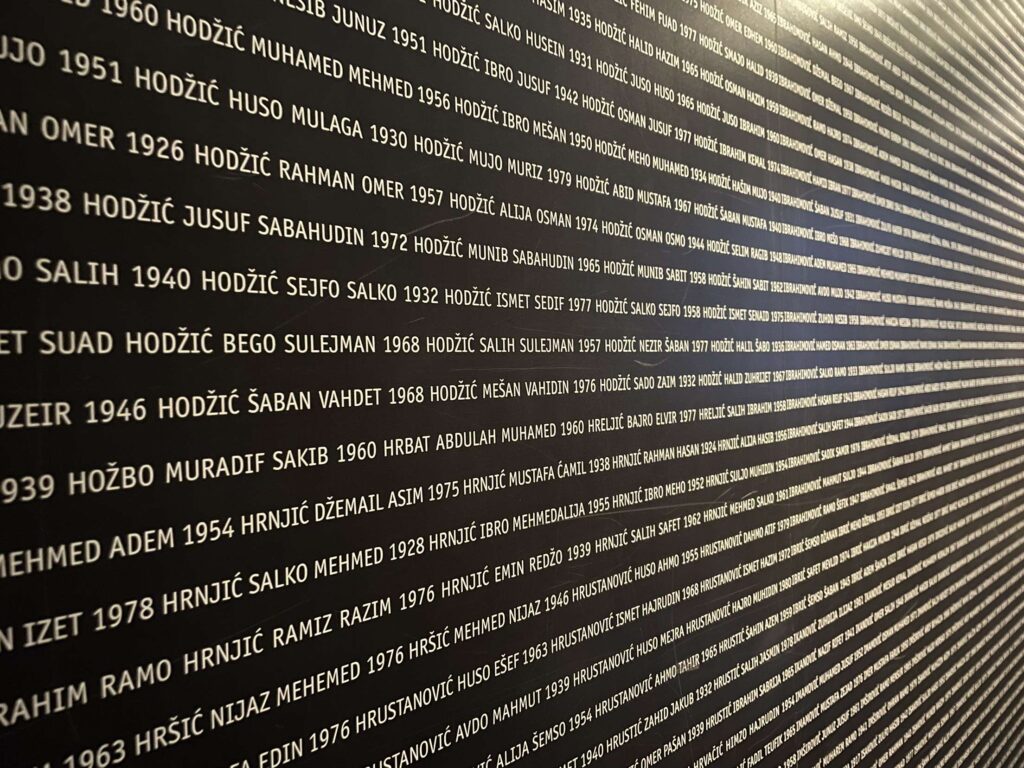

The first exhibition in Sarajevo we visited was by Tarik Samarah which displayed photographs of the victims of the genocide. The poignant display entitled the ‘Srebrenica Genocide Memorial Exhibition’ in the 11/7/1995 Gallery, displayed photographs of the victims who never returned home. Many of these had been donated by grieving mothers, and included photos of men and boys of all ages. Samarah’s photos also showed the aftermath of the killings, images of rows of skeletons and graffiti left by Dutch soldiers.

Upon entry to this exhibition, the wall ahead of you contains all 8,372 of the victims of the Srebrenica genocide, alongside the years of their birth. The youngest person we saw on this list was 8 years of age. This brought home to us the sheer scale of what we were going to see on our trip.

Siege of Sarajevo Museum

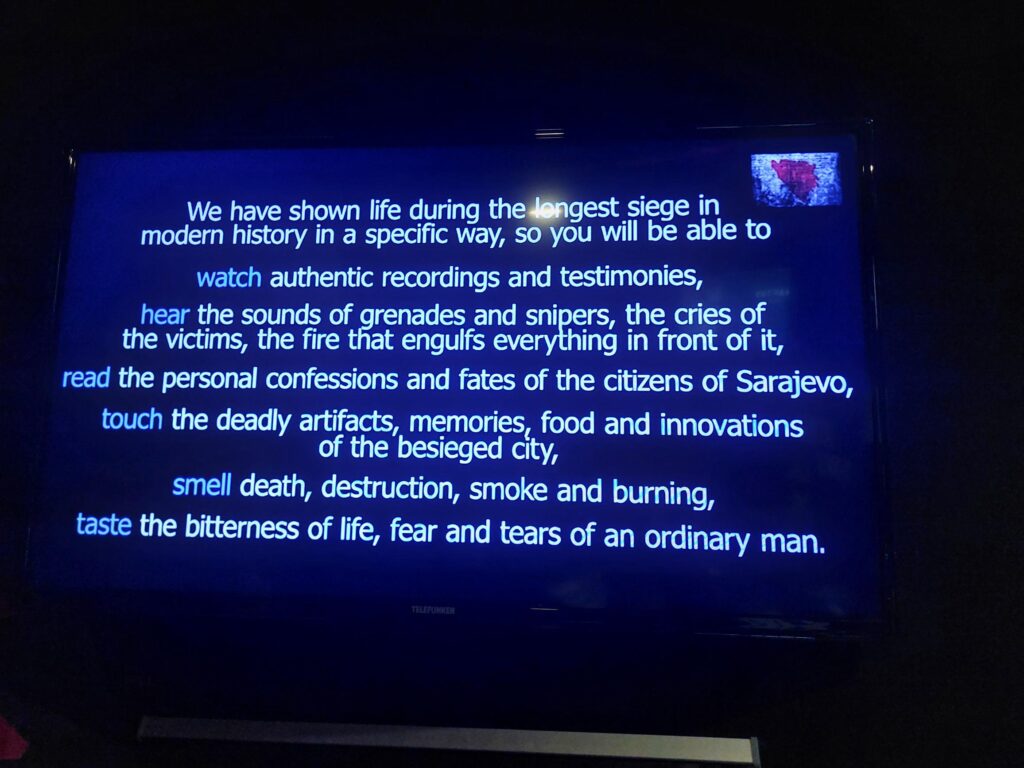

On a visit to the Siege of Sarajevo museum, which is dedicated to the experiences of those who lived through the tragedy, we were greeted with a sign that encapsulated the way many of the museums we visited were presented.

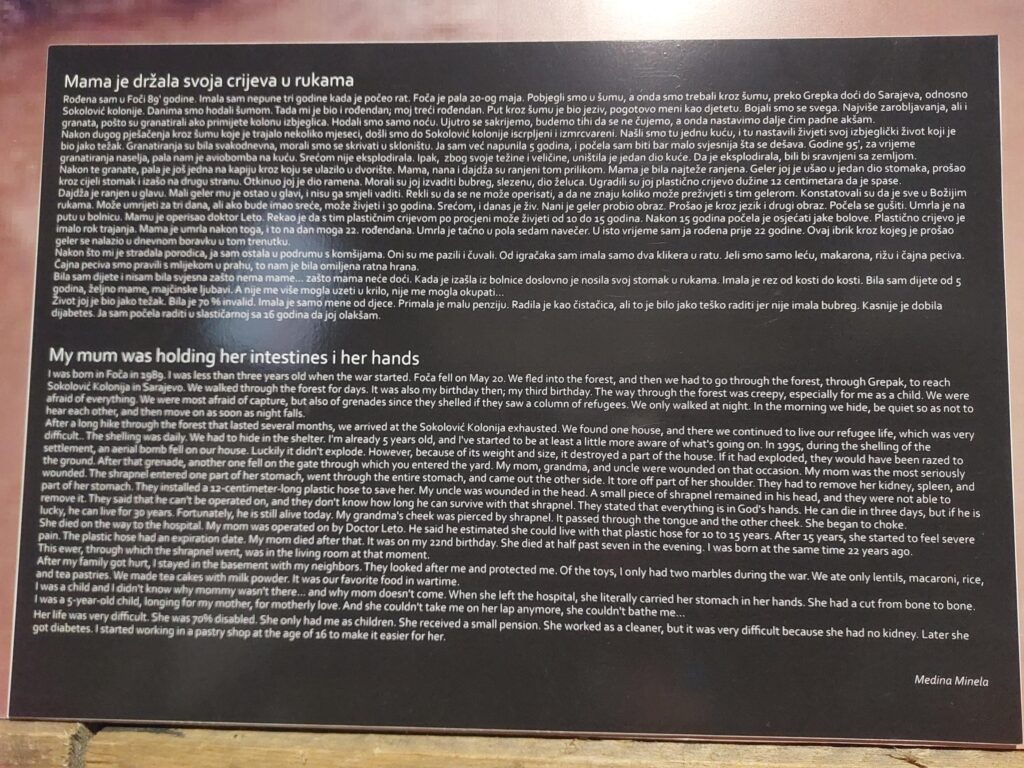

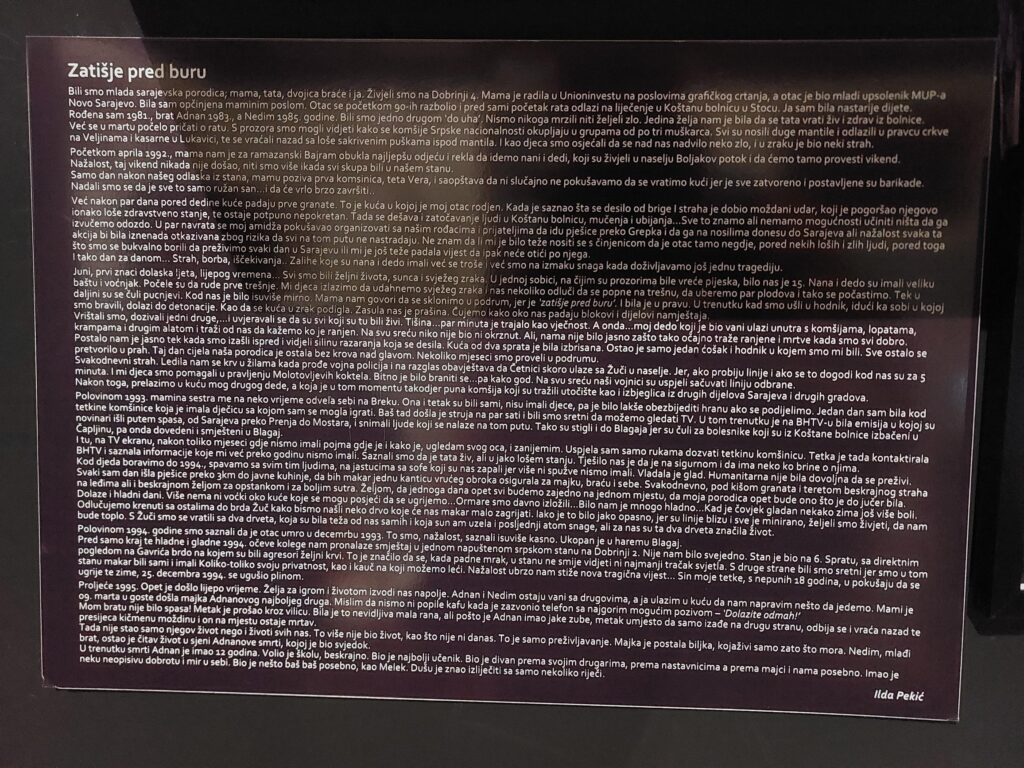

The graphic nature of the museums was a common theme we observed across all the institutions we visited. Exhibits with blood on them and images of children moments before their tragic deaths were poignant but painful things to witness. The museum’s presentation predominantly took the form of life stories alongside possessions of the person each story described. These gave a powerful insight into the everyday occurrences of war. Stories of parents reluctantly allowing their 15-year-old sons to defend their city powerfully illustrate the sacrifices everyone made. The photos below are just a few of the panels within the museum and items from the exhibition.

Museum of Crimes Against Humanity and Genocide

The Museum of Crimes Against Humanity documents the experiences of those who lived in Bosnia throughout the conflict, and contains stories and items from the camps where Bosniak Muslims were housed during the war. This museum was a powerful reminder that concentration camps were still used to house prisoners as recently as the 1990s. This museum also commented heavily on the UN’s involvement, with exhibits and items involved in the humanitarian effort on display, as well as stories from Dutch soldiers and their perspectives on the events. This museum also had a room where visitors could leave messages of hope. Many of these focused on current conflicts, but also reflected on the effects the museum had on them.

Our visit to Bosnia taught us a lot about the realities of living through modern warfare and that the memory of these must be kept alive. We hope that our visit to Srebrenica can help people remember and honour every one of the 8,372 victims of the genocide.

Holocaust Memorial Day

Holocaust Memorial Day came about following a request from Andrew Dismore MP to Prime Minister Tony Blair for such a day in 1999. The Prime Minister responded, mindful of the ethnic cleansing witnessed in the Kosovo War at that time:

“I am determined to ensure that the horrendous crimes against humanity committed during the Holocaust are never forgotten. The ethnic cleansing and killing that has taken place in Europe in recent weeks are a stark example of the need for vigilance”.

In the following year, representatives from 46 governments around the world met in Stockholm to discuss Holocaust education, remembrance and research. The declaration they signed formed the basis of the 27 January 2000 Statement of Commitment that was adopted for Holocaust Memorial Day. In 2004 the United Nations voted, by 149 votes out of 191, to formally commemorate the Holocaust atrocity. 27 January was chosen as it was the date on which the largest Nazi death camp, Auschwitz-Birkenau, was liberated in 1945.

An Act of Remembrance for Holocaust Memorial Day has been held in Cheltenham every year since 2001. With members of Cheltenham Hebrew Congregation, Three Counties Liberal Jewish Community and Cheltenham Borough Council co-organising the event. This year, we will also be involved in an event at the Cheltenham Municipal Offices on Monday 27th January. Details can be found here.