| History

The Naga Labour Corps

This post comes from Ed Barrett, PhD student in Illustration and History at the University of Gloucestershire.

About the project

The Naga Labour Corps [NLC] was a group of companies of men from the Naga Hills in North-East India who went to France in 1917. Their contribution to the war effort included vital salvage work and road building. However, they – like much of the rest of the various Labour Corps – have since been largely forgotten in the West.

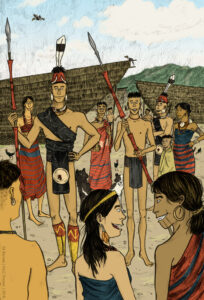

I found out about the NLC on a trip to the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, where there is a pickelhaube that had been taken home by a Chang Naga, who had turned it into a dance-hat. I wondered who might think that a German helmet could be repurposed in such a way, and wanted to find out more. This project grew out of an earlier version that was part of my MA in Illustration, and I intend on taking it further after completing my PhD. My visual interpretation of the experiences of the NLC follows four fictitious Labour Corps men who I use to explore alternate viewpoints. One of the difficulties with this project was finding visual references. It’s relatively easy to find photographs of warriors since anthropologists tended to focus on them, but they didn’t take many photographs of anyone else, including women at different social levels. In the future version of the project, I’d like to ask Naga people whether they could help by contributing images of their own. My artistic influences are mainly contemporary with the First World War, such as illustrator Bert Thomas, who made propaganda posters and cartoons; the Nash brothers, Paul and John; and Percy Wyndham Lewis and the Vorticist movement.

About the Naga Labour Corps

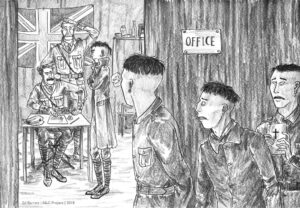

In January 1917, Austen Chamberlain, Secretary of State for India, discovered that 50000 men from South Africa had been sent to France as the South African Native Labour Corps. He wanted to send an equal number of men from India to serve as the Indian Labour Corps. From about February 1917 through to early summer that year, a recruitment drive was carried out across India. The British informed people that joining the Labour Corps would allow them to travel to Europe, and that any man who joined would be exempt from paying certain taxes.

The men signed a contract stating that they would serve in the Labour Corps for a year. Some deliberately requested to be sent to Europe. In addition to having medical examinations, and being given uniforms, they were drilled for a few weeks on how to march in formation, how to react under fire, and how to cross roads in cities.

After an introduction to military life, they made their way to the sea, which most had never seen before. At the Gulf of Taranto, they boarded a train for Marseille. From there, they were sent on to places such as Arras, where some were photographed by Lt. J. W. Brooke, and to the supply centre at Abancourt. In addition to portering and constructing camps and trenches to help release British troops to go to the front, some NLC companies also built roads and collected salvage from battlefields. This is probably where the Chang Naga man acquired the helmet that became a dance-hat.

In January 1918, the War Office wanted to extend the Indian Labour Corps’ contracts from twelve months to the duration of the war, but many companies, including the Naga Labour Corps, refused to sign. They were due to be sent home in the spring, and didn’t want to spend any more time in France than necessary. Following action by the ILC, including strikes and an alleged threat of arson, they were informed that they would be sent home. At the end of May, the NLC set sail for India.

On their return, festivities were held to honour the returning warriors. Despite their non-combatant role, in their own culture they were perceived as warriors. Lord Ampthill, Director of Labour, tried to have the Indian Labour Corps reclassified as combatants due to the dangerous nature of their work.

What’s next for the project?

I intend to broaden my coverage of the subject, including to the Naga Club, the Kuki Rising and the Manipur Labour Corps, which seems to have involved Nagas from various tribes. I’d like to collaborate directly with Naga people. This is part of their heritage, and the story of the NLC is connected to the creation of the state of Nagaland. I’m now in contact with a few people from the Naga tribes – scholars, historians, and relatives of Labour Corps men – via Instagram, after I posted some of my Labour Corps drawings. I’ve already learnt a great deal from them.