| History

Thinking about Wateryscapes

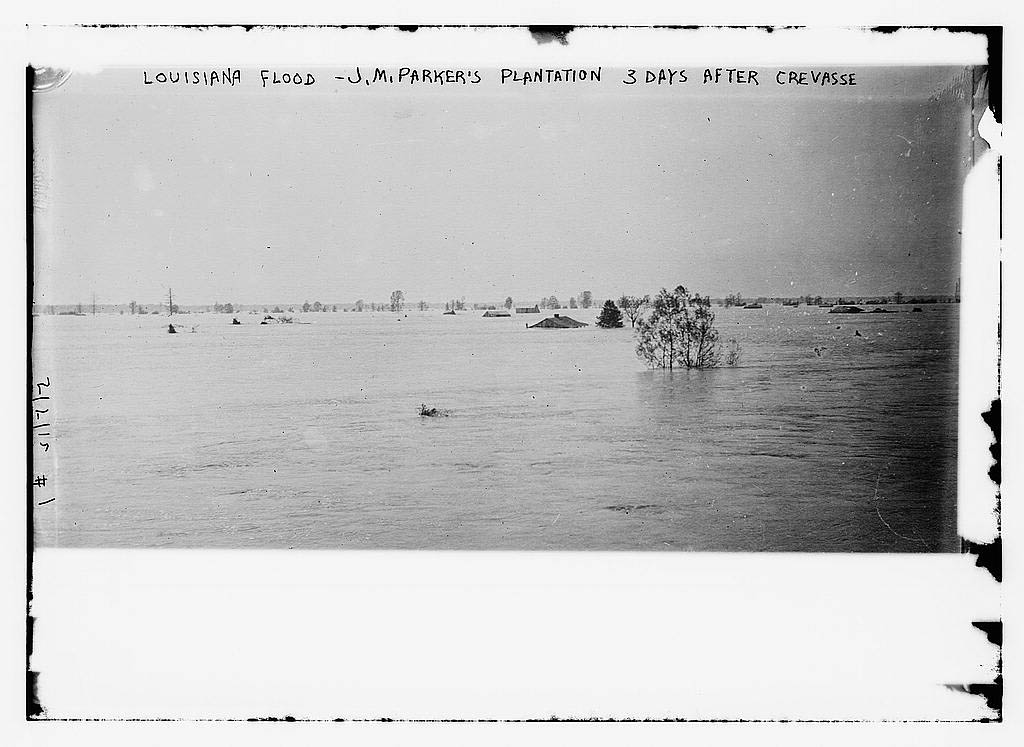

How often when we think of a landscape do we imagine it wet? It is nearly always dry; nearly always ‘England’s green and pleasant land’. But for many people, both now and in the past and certainly into the future, the landscape they interact with is often wet. Think of the Fens, of the Somerset Levels and of anywhere close to the Severn. Think, too, of the Gloucester floods of 2007 and of many other communities into the future: all can find common ground with the sentiments expressed so eloquently by Adam Nicolson below.

How often when we think of a landscape do we imagine it wet? It is nearly always dry; nearly always ‘England’s green and pleasant land’. But for many people, both now and in the past and certainly into the future, the landscape they interact with is often wet. Think of the Fens, of the Somerset Levels and of anywhere close to the Severn. Think, too, of the Gloucester floods of 2007 and of many other communities into the future: all can find common ground with the sentiments expressed so eloquently by Adam Nicolson below.

But aren’t floods and flooding just a bit too topical and recent for a history blog? Well, very obviously no! Floods and flooding have always been with us from the Biblical flood onwards; they have always formed a central part of our life experience and story-telling. And, as the most recent episodes clearly indicate, we in Gloucestershire do not have to go far to find flood narratives. Alongside colleagues in this University and the University of the West of England I have been involved in a research project attempting to capture some of these narratives, mainly from the ‘big’ event of 2007 when much of the area was without power and clean water for a considerable period of time.

Prior to that it was 1947 that is remembered as the worst flood. Here’s one of our oldest interviewees recalling her experience of this particular event: “It was right in the middle of a field. I can remember opening the door and there was this noise, “pshhh” and I said‟ “what is that noise?” and I looked out, and water was absolutely gushing.” (Mrs J. Conrad, Elmore Back)

And here’s an extract from the Church Vestry minutes, also from Elmore but this time from 1770. “On Saturday ye 17th of November … the Severn was greatly swelled by a very heavy Rain, which being stopped by the tide ran clean over the Sea walls above two miles length in this Parish, and Occasioned the most frightful inundation that ever was known here by any man living … indeed the Scene this Day was truly affecting; some in Boats leading Beasts half-drowned out of their once dry Grounds; Others picking up their household Goods which were now afloat … almost all the Cyder both new and old was damaged … There was happily no Lives lost … There was a very good Crop of Wheat the following year about the Back notwithstanding.”

I just love the reporting of no loss of life coming almost as an afterthought after the ruining of the cider! But more seriously the anonymous writer of this extract (most likely the vicar) reminds us that for some areas flooding is an intrinsic part of people’s way of life. The flood of 1770 brought alluvium, increased fertility and a good crop the following year in its wake.

The landscape of much of the parish of Elmore – experienced by a bunch of our first year students on a (thankfully dry) field trip just before Christmas – is very similar to that of the Somerset Levels which we are currently hearing so much about. So, too, is the way of life on the Levels. My final extract eloquently captures something of the experience of living in a watery landscape.

“When the water in the River Parrett stays high for a few hours … it seeps out through the river bank and into Harold Hembrow’s garden in Burrow Bridge … No water comes into the house itself, which is only a yard or two from the river bank, but the line of damp on the wallpaper climbs towards the ceiling throughout the spring and early summer each year … lifting above the furniture at Easter, reaching the top of the windows by June … Wetness is not a substance but a quality that seeps and leaks into everything like a stain.” (Sutherland and Nicolson, 1986, p.1)

I’ll sign off with two questions:

- Can history tell us anything about future sustainability and preservation of ways of life in the face of climate change?

- What can be the role of memory when the way of life it feeds and feeds off is no longer with us?