| CC4HH

Legacies of slave ownership in Gloucestershire

This project was conducted by Harry Scott, Joe Richardson and Stephen Walmsley.

Jump to: Legislations | Legacy 1: Hobbies and interests | Legacy 2: Investments | Legacy 3: Stately homes in Gloucestershire

The Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 not only highlighted the ways in which racism continues to influence the contemporary world, but also raised significant questions about the way we discuss, remember, and often forget the history of the transatlantic slave trade. This project focuses on this history to see if a better understanding of the subject can help to heal social divisions. It takes a local focus by tracing the legacies of slavery evident in Gloucester and the surrounding area and it examines the compensation slave owners received when slavery was abolished.

Legislations

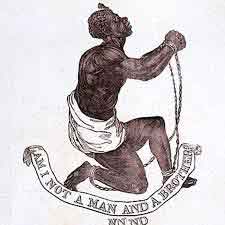

While campaigns for abolition had existed on both sides of the Atlantic for decades, two key pieces of legislation brought the practice to an end in the British Empire:

1: 1807 Slavery Abolition Act:

Whilst not emancipating enslaved people, the act banned the transatlantic slave trade. British ships now confiscated vessels found trading human beings and imposed fines of £100 per enslaved person on board. It also granted some liberties to freed slaves, but these were limited.

2: 1833 Abolition of the Slave Trade Act:

This act emancipated enslaved people and compensated slave-owners for their ‘loss of property. Over 3000 families received compensation for slave ownership. Many beneficiaries were absentee landlords or shareholders in plantations. In total, around £20 million (£17bn today) was spent on compensation claims, around half of which remained in Britain. This accounted for around 40% of the national budget at the time and the debt was only finally paid off in 2015.

This tweet had to be removed following negative backlash. Did you know your taxes had been used to compensate slave owners? Do you agree with the reaction?

Records from UCL’s Legacies of British Slavery database indicate that there were approximately 400 awardees of compensation in the county. The compensation was spent in many ways and is still traceable today.

The following project provides examples of how some of those compensated locally used their funds in three main ways:

1) funding personal interests, hobbies and travel; 2) making financial investments; 3) buying and / or renovating country estates.

We used the Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery throughout this project.

Legacy 1: Hobbies and Interests

George wilson Bridges (1788-1863)

Bridges’ connection to slavery demonstrates several important and complicated elements. Bridges was a Reverend, and served as a Vicar in two parishes in Jamaica: Manchester and St Annes. Whilst there he earned up to £2000 a year by baptizing enslaved people (£136,000 today), highlighting the complex relationship slavery had with religion.

He also owned three domestic slaves for which he received £87 in compensation (£5600 today). He later served in two Gloucestershire parishes, Maisemore (1844-1846) and Beachley (1858-1863). He wrote several books in which he forcefully defended slavery and the empire.

George Charles Grantley Fitzhardinge Berkeley (1880-81):

Berkeley served as Whig MP for Gloucestershire West from 1832 to 1852. He received £14,545, 17s, 4d in compensation for two slave plantations in British Guiana (equivalent to £878,818.38 today), he was forceful in his opposition to the abolition of slavery. His legacy includes many publications, the most famous being Berkeley Castle (1836). In total, he published 8 books and 8 pamphlets on topics including sports, politics and general life.

These are just two examples of local figures who received compensation and went on to influence public life in different ways. Many others sought to increase their wealth even further by reinvesting their compensation money into business ventures.

Legacy 2: Investments

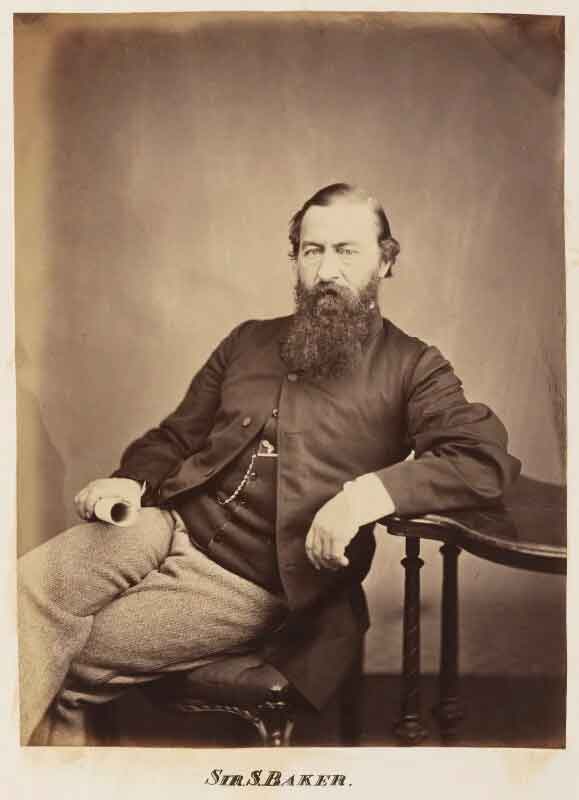

Samuel Baker (1794-1862):

Baker is one of the more well-known figures amongst those who had a strong connection to the slave trade.

Arriving from London in 1832, alongside his business partner Thomas Phillpotts he was responsible for the construction and development of ‘Baker’s Quay’, now known as Gloucester Quays.

Baker’s Quay enabled the shipping of goods from the Caribbean directly into the city.

Baker and Phillpotts made various adjustments to the quayside, such as widening the quay wall and building various warehouses, changes that benefited local businesses and members of the public.

Baker is associated with two compensation claims (one shared with Phillpotts) for two plantations in Jamaica totalling nearly £8000 (over £900,000 today) which covered the ownership of 410 enslaved people. He invested heavily in the railway companies around the areas of Gloucester, Worcester and the Forest of Dean.

He died with a wealth of £30,000 (c.£4,000,000 today). He left his Barbadian sugar plantations to his son, Sir Samuel White Baker, who became a famous African explorer and was celebrated for his abolitionism, which often hid deeply racist views.

Henry Sealy (d.o.b. unknown – 1864):

Sealy owned four plantations in Barbados. He received around £400 in compensation for two of these estates, and was unsuccessful in his other two claims. He invested £2500 in the York and Carlisle railways.

Additionally, Sealy’s mother Sarah benefitted from these two successful claims which covered the possessions of 18 enslaved people. The family were originally from Gloucester but spent time in Barbados, where Sarah married William Sealy. The family later moved to the prosperous Clifton area of Bristol.

These are just two examples of the way in which profits directly or indirectly connected to slavery were invested in public works and infrastructure. In fact, much of the research on these legacies demonstrates that it was very common for money to be reinvested in the railways. However, some preferred to invest in property.

Legacy 3: Stately Homes in Gloucestershire

Another indicator of whether a family was involved in the slave trade was through the ownership of stately homes and country estates. As research by English Heritage and scholars such as Madge Dresser and Andrew Hann has uncovered, some of the money earned from slavery and/or compensation was reinvested in the development and renovation of stately homes. Some of these estates are highly respected today and have been granted protection by the National Trust. At the time of abolition, there were around ten key country estates located in Gloucestershire that saw money from compensation used to renovate the grounds.

Country estates with connections to money from slavery:

In 1690, the Hayward family purchased the Quedgeley estate. They also owned a 200-acre plantation, Brewer’s Bay, in Tortola, British Virgin Islands.

Cirencester Park was owned by the Bathurst family who had a long association with the slave trade. The estate was purchased in 1700 by the first Earl of Bathurst, Benjamin Bathurst.

He was also a high-ranking official in the Royal African Company. Descendants of the first Earl were more sympathetic to ideas of abolition.

The strong links with the slave trade are also evident in the fact that ‘there are many Bathurst place names throughout the Empire, especially in Jamaica. (Dresser & Hann, Slavery and the British Country House, English Heritage, 2013).

The Royal African Company (RAC)

The scale of the slave trade expanded and was encouraged in part by the granting of royal charters to private companies. Originally set up by the Stuarts, the RAC was given a chartered monopoly over the English slave trade by Charles II in 1672 and created trading posts supported by the army and navy. For nearly a century afterwards, the RAC dominated the transatlantic slave trade, and was responsible for shipping more African slaves than any other single organization in the history of the trade.

Lydney Park (near Lydney) was owned by another branch of the Bathurst family (Charles Bathurst) after it was purchased from the Winters family in 1723. Both families had links to the slave trade.

Cleeve Hill House was originally owned by Charles Bragge, later known as Charles Bathurst from 1804. Charles Bathurst eventually inherited the Lydney Park Estate.

Barrington Park (near Burford) was purchased in 1734 by Charles Talbot, a Lord who served as Attorney General in 1729. As Attorney General, he was joint author of the infamous York/Talbot judgement of 1729:

‘Their opinion… was that a slave in England was not automatically free, could be forced to return to the colonies from England and that Christian baptism did not confer freedom to a slave.’

Dresser and Hann, 2013

Lypiatt Park (near Stroud) was owned by Samuel Baker (discussed above). As Dresser and Hann demonstrate, Baker purchased the property in 1838, after he had been compensated for the loss of over 400 enslaved persons.

This once again highlights how the wealth generated by slavery found its way onto British soil. Baker willed the property to his son, Samuel White Baker.

Why does this history matter?

This project has enabled us to gain an insight into the deeply entrenched legacies of the slave trade, and particularly how the wealth generated by slavery and its abolition was used in different ways.

Our findings challenge the idea that slavery was simply something that happened a long time ago and somewhere far away.

As our examples highlight, even at a local level, it is possible to trace links to the transatlantic slave trade. This history is very much a significant part of both the British past and the present.