| CC4HH

Fashion & Textiles: A Gloucestershire Story

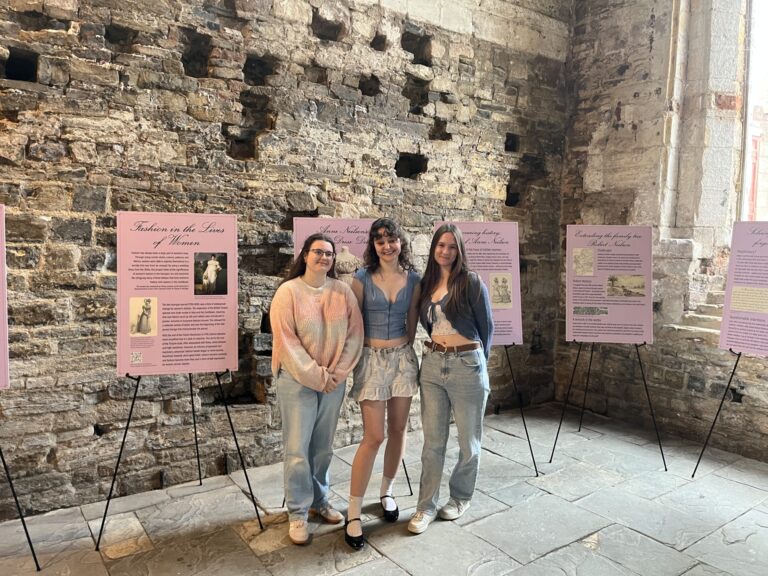

To celebrate the Museum of Gloucester’s costume collection, this exhibition, by University of Gloucestershire History students, takes a look at the history of Gloucestershire’s textile industry from the 17th to the 21st centuries. It explores the effects of the Industrial Revolution, royal influence, gender and imperial trade on textile manufacturing. The exhibition took place at the Museum of Gloucester in 2023.

Jump to: Women’s fashion in the 1800s | Men’s fashion in the 1800s | Gloucestershire Wool and ‘Strouds’ | Trade of British Cloth | The Industrial Revolution and its effects | Responses to the Industrial Revolution | Factories and Clotheries in 20th Century Gloucestershire | Factories and Clotheries

Fashion in the 1800s – Women’s Clothes

Changes to women’s fashion during the 1800s were reflected in hemlines, waistlines and hats. By the beginning of the 20th century, dresses were made of linen and lace, with flouncing and ruching with embellishments to emphasise the backs with a bustle, alongside the use of trains.

In corsets, supporting materials changed from horsehair and whalebone to metal strips. By the 1840s, women were wearing light metal hoops in crinoline dresses with many petticoats: a metal cage was worn underneath the bell-shaped skirt. By the end of the century, sleeves became tighter, necklines were higher, and skirts were smaller and A-line. Accessories formed part of the outfit: trimmed hats, worn squarely on the head, and parasols.

ROyal influence on fashion

Queen Victoria requested that her clothes and those of her courtiers should be made in Britain. This increased demand for mass-produced clothes with flouncing, ruching and embellishments. The bell-shaped dress was introduced in the Victorian era, moving away from the wide skirted dresses of the Georgian period and the high waistlines of sleek Regency style dresses.

Following the death of Prince Albert, Victoria remained in mourning attire from 1861 until her death in 1901. Mourning dress was plain and conservative, with more elaborate and strict rules: veils and drop earring became increasingly common. The Workwoman’s Guide (1840) detailed expected mourning times for close relatives.

“Advances in textile manufacturing combined with a new consumer appetite for mourning apparel led to the establishment of stores – like Besson & Son in Philadelphia and Jackson’s Mourning Warehouse in Manhattan – that sold ready-made mourning clothes, while department stores like Lord & Taylor added mourning departments.”

Jocelyn Sears for Racked.

History of nurse’s uniforms

Nursing was acknowledged as a profession during the 1800s. Florence Nightingale defined the nurse’s uniform. Influenced by a nun’s habit and drawing on the use of ‘sister’, a nurse wore a high collared-shirt, floor-length dress and a bonnet.

During the 1900s, uniforms became more practical and began to distinguish the different roles and nursing hierarchy by using a variety of colours and symbols.

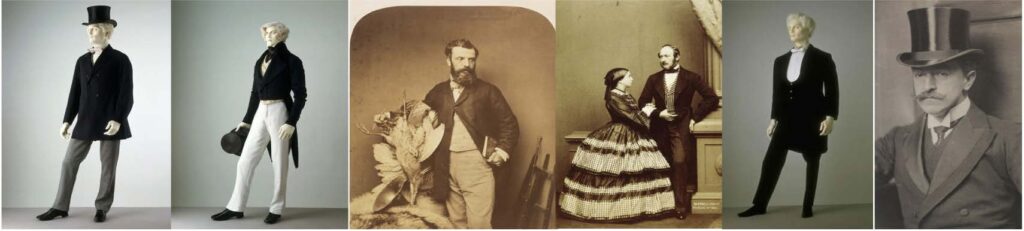

Fashion in the 1800s – Men’s clothes

In the early Victorian period, emulating Prince Albert, men wore jackets and coats with cinched waists, creating an hourglass figure. In the 1850s, collared shirts were worn with large bowties. Lower class men wore bowler hats (the working-class hat), while upper class men wore top hats. Jacket and coat length moved down from the hip to mid-thigh. By the 1870s, high-buttoned, semifitted jackets were popular.

The 1880s saw a move to buttoned waistcoats rather than jackets, now worn with neckties and bowties around high collars. By the end of the century, men moved away from frock coats (popular with more conservative dressers) as three-piece lounge suits

gained popularity.

Prince Albert’s influence:

In the 1850s, influenced by Prince Albert, men’s facial hair was shaped in large ‘mutton-chop’ side-burns and moustaches. Moustaches remained fashionable even after Albert’s death in 1861.

During the Crimean War (1853-56), many soldiers became infected, sometimes fatally, because of razor cuts. Soldiers began to sport long beards, and these became popular after the war following a trend started by veterans.

Gloucestershire Wool and ‘Strouds’

Although the Industrial Revolution resulted in the mechanisation of the textile industry, particularly cotton and worsted production, its impact in Gloucestershire was initially rather limited. The South West’s textile business was largely focused on more traditional woollen production.

Gloucestershire’s main product was broadcloth, produced on a broadloom and used for men’s suits and greatcoats. Manufacturers soon adapted to new fashion trends during the Napoleonic era that required lighter cloth by introducing light-weight cassimere.

Gloucestershire’s wool production dominated the English market in the 18th century, but its industry declined in the early 19th century. By the mid-19th century, it was surpassed by West Riding in Yorkshire, which sold cheaper woollen textiles of lesser quality.

Images below: Recreations of traditional broadcloth (left) and much finer cassimere (right).

International trade of Strouds

Taking off in the 1500s, Gloucestershire’s textile production focused on wool: white unfinished cloth was sold as far away as Holland and Germany. In the 1600s, the red broadcloth called ‘Stroudwater Scarlet’, among other dyed cloth, became especially famous. It was died with an expensive pigment, Cochineal, extracted from dried insects native to South America. It was often used to make the recognisable red uniforms; and a blue version, made from indigo, was used for naval officers.

Pictured: Dress uniform jacket of the Scots Guards made from Stroudwater Scarlet.

The cloth was nicknamed ‘Strouds’ and was exported by the East India Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company in the 18th century. A version of the cloth with a striped or white edge became sought-after among the native community in North America. The cloth became such a valuable item that it was often traded for land or even hostages. Gloucestershire textile production flourished until the 1720s. Competition and cheap imitations of the ‘Strouds’ led the trade into inevitable decline by the end of the 19th century.

‘In 1716 “Indian Peggy” appeared before the Commissioner of Trade with a “French man” purchased by her brother and given to her. The man had come dearly, costing her brother “a gun, a white Duffield match coat, two broadcloth match coats, a cutlass and some powder and paint”. Peggy was willing to exchange her hostage for the gun, and “the value of the rest of the goods might be paid her in strouds”.’

Interaction between a Native American and a ‘French Man’, showing how highly ‘Strouds’ were held by natives

The trade of British Cloth

The East India Company (1600-1874) oversaw the trade of cotton goods for Britain. As domestically produced calico and chintz were gradually substituted with Indian wool and linen, local weavers, spinners, dyers, shepherds and farmers petitioned their MPs to ask Parliament to ban imports of textiles and later the sale of woven cotton goods. This was achieved with the 1700 and 1721 Calico Acts.

In the 19th century, with support of Queen Victoria and her insistence on the use of British textiles, weavers and mills, Britain became the world’s leading cotton textile manufacturer. Ports on the west coast, such as Liverpool, Bristol and Glasgow, were important hubs for the cotton industry.

Trade in Gloucestershire

Gloucester canal and its railway network increased the county’s economic success with links to surrounding areas. In the 1800s, the ‘five-valleys’ of Stroudwater, Little Avon / Doverte Brook and the Ewelme / Cam had almost 200 mills.

‘In the mid 19th century, the trade brought by the Gloucester and Berkley canal was of primary importance to the economy, and the building of railways improved links with Gloucestershire’s hinterland.’

Gloucestershire’s main industries were timber yards, flour mills, engineering works and manufacturing, producing goods ranging from railway wagons to matches. With metal and engineering trades employing at least 434 people, the city also depended on the employment of builders, the provision of food and clothing, and domestic service.

By the 1830s, pin making, one of Gloucester’s staple industries, employing a largely female workforce, faced strong competition. The removal of patent restrictions led to its collapse. Of the surviving firms, one ceased production before 1841 and the other closed in the 1850s.

From the mid 1850s, Gloucestershire’s river and canal trade was assisted by steam tugs on the Severn river. Alongside new markets for cheese, wool, and hides established in the 1850s, a new produce market and corn exchange were built in 1856. Leather traders were represented by curries, fellmongers, a glover, saddlers, and numerous boot and shoemakers, one of which had 24 employees in 1851.

Pictured: Map of 1800s Gloucester

The Industrial Revolution and its effects

Weaving shops

Traditionally, small clothiers were part of the entire process of wool manufacture. They owned the materials they worked on, bought the raw unprocessed wool from local shops, processed it and sold the cloth they made. The introduction of Spinning Jennies and the flying shuttle by the 1790s meant that many weavers moved from their homes to larger workshops.

Purpose-built houses included weaving shops, often recognisable by their large multiple windows. These workshops were usually set up in one of the floors or in a building adjacent to the main house. The heavy broad looms had to be placed on the ground floor, whereas shops that worked cassimere were able to place the lighter narrow looms on the top-floor. Large mills and factories gradually mechanised the spinning process. Until the introduction of the spinning mule in wool factories in 1830, most yarn was still spun in weaving shops, meaning that some of the traditional shops survived into the mid-nineteenth century.

Changes in weaving during the turn of the century

Weaving remained a largely traditional enterprise until 1826. Most cloth mills did not include a weaving shed and handled the ‘preparatory process of carding, and scribbling, in spinning, and in the finishing process of fulling and dyeing and shearing’ . Large mills eventually drove the traditional smaller clothiers out of business by incorporating the various stages of cloth manufacture into one system of direct production. They became ‘loom factories’.

This system of mass production eliminated the need for skilled workers and forced skilled artisans to become factory workers. Weavers lost their independence. They began to work in factories, away from their home and families.

Gender in the Wool Industry

During the early modern period, women could be found in every process of wool manufacture. With the Industrial Revolution, however, some processes of wool manufacture became reserved for men. Wool-sorting, dying, pressing, scribbling and shearing were all mostly male jobs by the 18th century. One of the best paid areas of work for women in the textile industry was that of a handloom weaver. As such, women in Gloucestershire earned about as much as men and represented about two fifths of the workforce. Other female textile workers such as spinners, machine attendants or dressers, however, earned much less.

A significant gender wage gap was evident in factory work. Woman were excluded from high-wage jobs such as overseers, weavers or mechanics. Even in an all-female factory room, the overlooker was a man. Types of work were divided by gender, which made competition for equal pay significantly more difficult. Even if a woman’s occupation required skill and that of a man did not, the man wold be paid more than the women.

The wage gap was even higher in Gloucestershire than in other counties that produced wool. Consequently, fewer women than men were employed in textile factories in Gloucestershire. They were able to earn more by doing other work, specifically in agriculture. Despite this, on average, Gloucestershire women earned just about as much as women in other counties. They simply worked more in other areas of industry.

Responses to the industrial revolution

Strikes

The damaging effects of industrialisation were met with significant responses. Having lost their independence and ownership of the trade due to competition from large factories, there were a series of weavers’ strikes during the 1820s, with some turning

violent. With a high cost of living and low wages, weavers demanded a rise in average weaving rates and a national pay scale. After a muted response, they went on strike on 29 April 1825. They refused to go back to work unless new prices were agreed. More than

six thousand weavers congregated together several times. After some time, new prices were agreed and the weavers returned to work, but a few clothiers in Stroud could not or would not meet the demands. At the beginning of June, workers who had not retuned

to work seized cloth from those working, shouted insults and the strike turned into a riot. Perceived enemies were beaten and thrown in local ponds. Some strikers were arrested but the Tenth of Hussars had to be called from Bristol to disperse the crowds. The strike ended on the 6 June 1825.

Arts and Crafts against Mass production

In an effort to stand against mass production, a group of liberal craftsmen, including

William Morris, founded the Arts and Crafts movement. The movement included not

only painters, sculptors and architects, but also decorative artists engaged in tapestry,

carpet weaving, pottery, carpentry upholstery, bookbinding and letter printing, which were generally regarded as a lower art forms in Victorian times. The aim was to emphasise authenticity and to celebrate the designer and their obligation to produce the best work possible. They did not necessarily oppose machine production but saw machines as a tool to help in the crafts, with the worker finishing the product. Part of the movement settled in the Cotswolds. Architects Ernest Gimson and Sidney Barnsely moved from London with hopes of being more intimately involved with their products.

The Gloucestershire branch of the Guild of Handicraft set up workshops in Chipping Campden and hosted exhibitions in Cirencester. Today they are known as the Gloucestershire Guild of Craftsmen.

Pictured: Illustration of the Arts and Crafts workshop in Chipping Campden

Factories and Clothiers in 20th Century Gloucestershire

Despite the many challenges generated by the Industrial Revolution, Gloucestershire’s textile manufacturers and merchants continued to work and prosper.

Fishers’, Gloucester

A large costumer and furrier in 19th and 20th century Gloucester was Fishers’. They tailored ladies’ outfits and often advertised their affordable clothes with the caption ‘gange-petit’, meaning low-wage earners. French clothes became a dominant trend in fashion from the 1860s. Great couturier houses were built in Paris, the fashion magazine Vogue was established in the 1920 in France, and Coco Chanel rose to prominence in 1925. With the growing success of French fashion, Fishers’ often used French phrases in their advertisements. ‘Visit Notre Maison’ was used when they expanded their premises in 1917.

Geldart, Gloucester:

This ladies’ outfitters was situated on Northgate Street. They sold clothes throughout the first half of the 20th century. The Great Depression and World War II meant clothiers were forced to cut prices. Consequently, Geldart often advertised their stock with sales and bargains. The expansion of mass production also made clothes more affordable. The Gloucester outfitters bought their supplies from factories all across the UK. Their stock in 1945 included:

- Blouses form Lancashire

- Suits and underwear from London

- Knitted Sportswear from Nottingham

- Dresses from Newington

- Hoses from Leicester

- Gloves from Walsall

- Skirts from Bristol

Images below: Adverts for Geldart’s in the Citizen, 1936 and 1939.

Factories and Clothiers in 20th Century

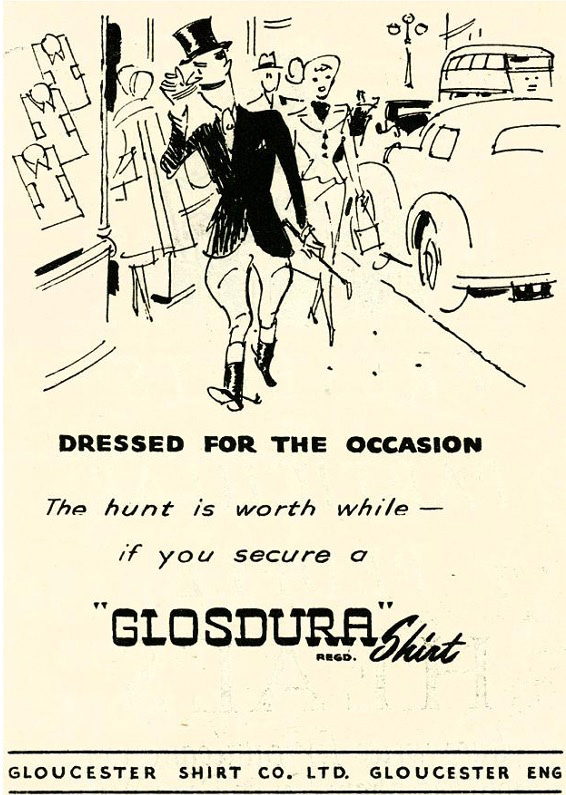

‘I must order some Glosdura shirts and collars!’

The Gloucester Shirt Company was counted amongst the larger textile factories in

Gloucester. Situated on Magdala Road, they supplied clothing across the country. Notably, they supplied London’s famous Savile Row tailors and the clothing brand Austin Reed. The ‘Glosdura’ shirt, the name under which shirts from the company were marketed, was advertised in newspapers across the country.

Although a stable part of Gloucester’s tailoring history, at times the local population

was not too happy. Having heard news of a planned expansion, the factory’s neighbours were worried about the high walls the company was intending to build. Several letters were sent to the Council expressing concerns about ‘air’ and ‘light’ being blocked from their gardens and windows. Nonetheless the Council approved of the expansion and building went ahead.

Heal Bros, Gloucester

Heal Bros was a long-standing draper in Gloucester throughout the 20th century. Located in Barton Street, they first focused on simple clothing items, such as curtains, blankets and table covers. Over the years Heal Bros increased their stock to include not only men’s and women’s fashion but also children’s clothes. When the co-founder, Mr George Peak Heal, died in 1962, he left more than £40,500 to his wife and children.

The store moved from Barton Street to Eastgate Street in the second half of the 20th century. It closed in 2018. Heal Bros is remembered by many Gloucester citizens as the supplier for their school uniforms.