| CC4HH

Remembering George Whitefield

This project was conducted by Frankie Stanley, Rebecca Chivers and Josh Oliver.

Jump to: Introduction | Early life | Religious works | Whitefield and slavery | Christianity and slavery | How should Whitefield be remembered?

Introduction

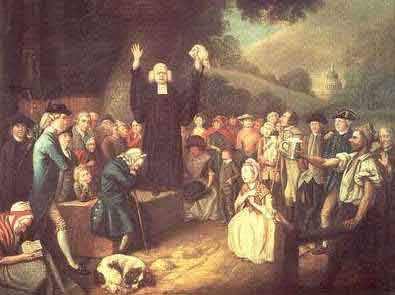

Gloucester-born George Whitefield (1714-1770), pictured, was a Methodist preacher. He became famous for his role in the rise of modern evangelicalism in Britain and the American colonies. He became known for his passionate and theatrical sermons.

In modern times, Whitefield is remembered as a devout Christian who brought a fresh approach to preaching that captivated and inspired thousands of people across Britain and the American colonies.

Whitefield’s story, however, also involves American slavery. He called for the better treatment of slaves, but later also became an advocate of slavery. He supported the movement to have slavery legalised in Georgia after it had been abolished.

Considering this complicated story, this exhibition explores the life and legacies of George Whitefield and asks: how should he be remembered?

Whitefield’s early life

Whitefield was born on 27 December 1714 at the family-run Bell Inn on Southgate Street, Gloucester. From an early age, Whitefield discovered that he had a natural affinity for acting – something that became crucial in his later life. He was educated at The Crypt School, Gloucester, and Pembroke College, Oxford. It was in Oxford that Whitefield met John and Charles Wesley. These three later founded the Christian Methodist movement.

After the Wesley brothers departed for Georgia in the American Colonies, Whitefield became the leader of their ‘Holy Club. He began preaching for the first time at the St. Mary de Crypt Church in Gloucester. His natural talent for theatrics shone through and enthused the listeners of his sermons. He quickly rose to fame.

In 1783 Whitefield set sail for Georgia to begin his preaching there, and to a specific audience: slaves.

Whitefield’s religious works

Whitefield was originally ordained as a deacon by the Bishop of Gloucester. He came to represent the close relationship between England and the American colonies and the role of religion. For 4 months in 1736, he preached throughout Georgia. He then started to raise funds to build an orphanage.

Whitefield was viewed as one of the colonies’ first celebrities. He travelled thousands of miles to preach to crowds in his condemnation of rationalist beliefs.

Whitefield’s sermons contributed to the Great Awakening, which had a lasting impact on American religious life and culture, and on Christian denominations.

“It grieves me to find that in every little town there is a settled dancing-master but scarcely anywhere a settled minister”

Whitefield in reference to North Carolina

Whitefield and slavery

Whitefield’s views on slavery changed throughout his life. He initially advocated for a better treatment of slaves. Writing to the inhabitants of Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas in 1740, he stated:

“I think God has a quarrel with you for your abuse of and cruelty to the poor Negroes… What a dreadful reflection is this on your Holy Religion? Unless you all repent, you all must in like manner expect to perish. God first generally corrects us with whips; if that will not do, he must chastise us with scorpions”.

In 1747, Whitefield’s Bethesda Orphanage faced closure due to the high costs of wages paid to white labourers in comparison to slaves. This brought about a shift in Whitefield’s thinking. He wrote to leaders of Georgia calling for anti-slave laws to be repealed: “Had negroes been allowed, I should now have had a sufficiency to support a great many orphans without expending above half the sum that has been laid out”.

When slavery was again legalised in Georgia, Whitefield wrote to Wesley in 1751: it is a trade not to be approved of … and [that it] lay a foundation for breeding up their posterity in the nurture and admonition of the Lord. Yet by the time he died in 1770, Whitefield owned around 50 slaves.

Christianity and slavery: a complex relationship

Pro-slavery Christianity

Many protestant leaders supported the enslavement of Africans and used scripture to justify it. In Scripture Relative to the Slave Population (1823), Fredrick Dalcho explained that humanity had fallen from grace: the negros, the descendants of Ham, lost their freedom through the abominable wickedness of their progenitor. Dalcho further claimed: Canaan’s whole race… were peculiar wicked, and obnoxious to the wrath of God.

Methodism and slavery

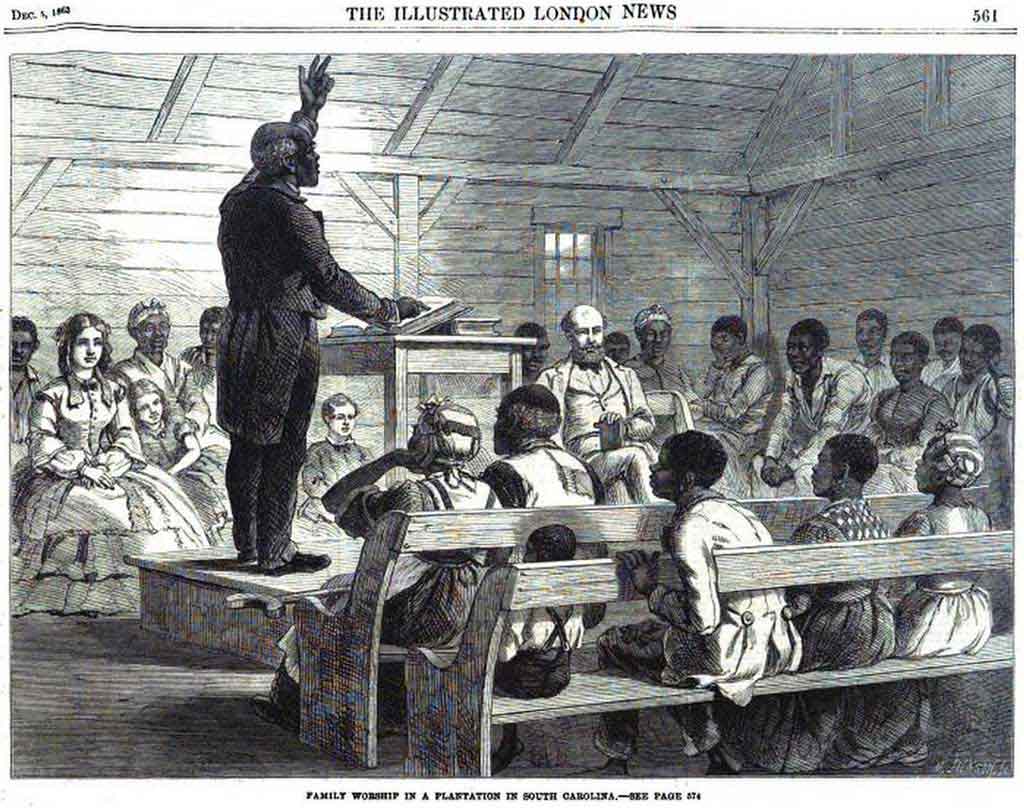

Many religious leaders saw Christianity as a way to improve the lives of slaves. Samuel Davies, Presbyterian evangelical preacher, wrote in the 1750s that there were ‘multitudes’ of Virginian slaves who are willing, and even eagerly desirous to be instructed, and to embrace every opportunity for that end.

Slave life and resistance

Slaves, however, adapted Christianity to their own cultural practices, and preachers played a central role in slave communities. They told stories that provided a means of survival and hope. John Thompson (the book about his escape pictured) claimed that religion gave him the strength to escape slavery: I knew it was the hand of God, working on my behalf.

HOw should whitefield be remembered?

Whitefield has primarily been remembered as an impressive orator and evangelist.

Why have his links with slavery been neglected?

Is it time to reveal a fuller version of his story?

“When I saw Mr. Whitefield come up upon the scaffold he looked almost angelic–a young slim slender youth before thousands of people and with a bold undaunted countenance…. he looked as if he was clothed with authority from the great God”

– The Spiritual Travels of Nathan Cole (1761)

The plaque on George Whitefield statue at the University of Pennsylvania includes a quote from Benjamin Franklin praising Whitefield’s ‘integrity’ and ‘indefatigable zeal’.