| CC4HH

Cheltenham diaspora: exploring narratives of migration into Cheltenham

The ‘Cheltenham Diaspora Project’ is a research project initiated and led by staff members at the University of Gloucestershire and funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund.

It has begun to unlock migration narratives in Cheltenham, celebrating diversity and adding unexplored elements to the history of the town.

Migrant communities have played a significant part in Cheltenham’s past and present, and the project has explored how people and communities have come to establish themselves in Cheltenham and the ways community heritage has evolved.

This culminated in an exhibition held at Chapel Arts in 2019. A series of events planned throughout 2020 were unfortunately cut short by the Covid-19 pandemic.

For those unable to make it to the initial exhibition, click on each section below to find out more.

Cheltenham: DIaspora

Migration is controversial yet universal.

Whether it is something we have experienced personally, through family, friends and even food, everyone has a connection to migration. Cheltenham is no different.

Most people are familiar with the Regency history of Cheltenham, but the story of Cheltenham is much more complicated and diverse.

Between 2018 to 2019, staff and students from the Cotswold Centre for History and Heritage gathered historical and contemporary stories of migration. Be it new starts from Brazil, sports stories from Barbados, cultural influence from China, tales of escape from wartime Poland, legacies of education in Nigeria, or the building of new lives from South Africa, the Diaspora project has scratched the surface of a huge global legacy surviving in Cheltenham.

The Cheltenham: Diaspora project aimed to explore and give voice to some of the stories of migration that have helped to shape the Cheltenham we know today. We also wanted to identify what forms of intangible heritage have travelled with people, and survive in Cheltenham today. What we have presented here is only a small sample of the many themes we have discovered so far.

We know that this is only the beginning and there are many more stories to collect. Around the exhibition, you will have the opportunity to share your memories, and we encourage and invite you to do so.

We want to hear your experiences of migration

Migration never ends. People will always move. The histories that come with migration are fragile, easily forgotten and lost.

As communities become more mobile, it has perhaps never been more important to record and curate the legacies of a transformative process. We hope that we have played our part in safeguarding those stories.

This project was supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund. We would also like to extend our thanks to every individual, community and organisation to have opened their doors to us, and shared their stories.

Flags of nations represented in this project so far:

University of Gloucestershire plays a major role when it comes to migration in Cheltenham. In 2018, the university attracted over 600 international students from over eighty different countries. This connection to the wider world is nothing new. When education was first provided on the Francis Close Hall site, in the form of the Cheltenham Training College in 1847, international students were often present.

The earliest international student that we have found in the university’s special collection archives, is Alister Mercier. Alister came to Cheltenham from Antigua in 1887, as a 21 year old private student. He would have received training to be a teacher.

We have found evidence for students attending the college from all over the world. In 1885, Francois Guillote joined the college. He joined from L’Ecole Normale de Mustapha, Algeria. In the same year, Thomas Tsing from Sierra Leone also attended the college. He was 22 years old when he joined from the Grammar School in Free Town.

There was a connection between international students attending the training college, and British colonial interests. William Robertson came to study from Trinidad. In 1862, Carapit Johannes joined from ‘Nassik, Bombay’.

Our biggest challenge remains finding more information about our former students from ‘Siam. Before Siam became Thailand in 1932, a number of students spent time in Cheltenham who are recorded only as being ‘Siamese’. This includes Siri Hai (or Nai) who attended in 1903, and Tongsook in 1907. The official college records provide no other details on these students. Finding out what happened to these students may prove to be impossible. We will, however, keep searching for them.

For many people who experience migration, the importance of certain objects can be profound. Often migration does not allow for many, or large items to travel; many people bring with them only what they can carry, and that which is personal. Often, it is the simplest objects which hold the most power.

As the ‘Cheltenham: Diaspora’ project grew, we were surprised by how large the South African diaspora was. We have interviewed more South Africans than any other cultural group, and every single participant mentioned the potjie.

The potjie, pronounced poi-kee, is a small, three legged, traditional iron cooking pot. The word potjie translates to ‘small pot food’. The type of food prepared in a potjie tends to be stew like meals, things that take a long time to cook. Like the traditional braai, the slow grilling of meat, the potjie is as much to do with social gatherings as it is to do with the actual meal.

“People say they miss that, the informal gatherings that happen in people’s homes. This is often focused on sport, around rugby and cricket, and the braai and the potjie goes with that. Here (UK) you can’t go to someone’s house without them knowing, it’s not done, and the South Africans don’t like that”.

“In South Africa, we love our barbeques, and a potjie…so in December, instead of cooking a Sunday roast, my kids were outside, in the rain and the wind, cooking a potjie…the cast iron pot gives it a completely different taste”.

The potjie, and other traditional forms of food, can become a powerful form of nostalgia.

“A lot of families do do them [potjie)]..and we used to go to these festivals where there were potjie competitions…Since coming here [to Cheltenham] we did have one, but we never used it. It was this massive pot and it was lovely to look at and think of home”.

For some South Africans, the importance placed on certain cultural practices such as the potjie, can be seen as a negative.

“You know you’ll hear of South Africans, when it’s snowing…and they go up to the roof of their building and they’ll have a braai, cook boerewors, drink beer, brilliant, which I think is great, but it shouldn’t be what defines you…

If I had to categorise those Saffers who have integrated well, or those who are not so happy, those who are less happy are very attached to their potjie”.

What objects have you travelled with, or would you travel with?

How important is it to keep cultural practices going from where people came from, or is it more important to ‘conform’ to where people are going?

One of the most challenges aspects of Diaspora was researching the stories of ayahs who lived and worked in Cheltenham.

Ayahs frequently came from India and China (known as amahs). Ayahs were women, employed by wealthy families to accompany them on long journeys. Ayahs essentially worked as nannies. They were paid little to nothing, exploited and often abandoned.

There are many records of ayahs in Cheltenham. A key reason for this was Cheltenham’s deep connections with the East India Company. Many families would travel between Cheltenham and India, and reliable ayahs were much sought after to help on the long voyage.

One of the most well known references to an ayah, is that of Ruth. Ruth is recorded as having been baptised at Christ Church, Cheltenham, in 1882, while in the employ of the Rowlandson family. The baptism took place in the Tamil language.

However we know little else about the life of Ruth. The names given to ayahs often had little to do with their birth names, while many who worked as ayahs were cut loose by their employers once their journey to the United Kingdom was completed. An ‘Ayahs Home’ was established in London, to provide care and refuge for the women deserted by their employers.

This makes tracing their personal stories difficult, at times impossible. However, we have identified several names in local archives, of ayahs, their children, and those who employed them, which might allow us to find out more about these women who travelled so far, to look after the wealthy youth of Cheltenham.

The English in India

Cheltenham Chronicle, 1863: “During the past and current year great work had been done and much progress made in India.” Col Rowlandson: “In a place like Cheltenham, where he was led to understand there was a good deal of the Indian element, he thought if it were the case, the society ought to receive support. He asked why did God give us that great land in preference to Portugal or Holland? Was it to gratify the interests of Englishmen or the English nation? He thought not, but simply that they might plant His Church there, in order that His word might prevail. (Cheers)… he believed the missionaries were the best policeman they had in India..”

Religious practice is one of the most common forms of intangible heritage. Religion and places of worship can be critical for individuals and communities coming into new areas.

However, a challenge often faced by migrating communities is in finding a place to worship. As migration from India to Cheltenham grew in the 1970s, many activities associated with mosques took place in people’s homes.

Cheltenham Mosque:

“My grandad, and a couple of other grandads, originally came over from India….they started a mosque here in the 1970s…we started with mosque classes, which were held in a house in Granville Street just across the road (from the current mosque). That was my uncles old house”.

Hindu Temple:

“Well I’ve been here since 1969, and the Hindu community first started to grow around the 1950s, but it was only around 1986 that we secured this place [the former Mission Hall on Swindon Road]. Since then it has grown with the help of our community”.

As places of worship grow, they can become cultural focus points for people migrating into new areas.

Cheltenham Mosque:

“In the 1990s, I remember it was just Gujaratis, a specific type of Indian community. There are a lot of Bangladeshi communities now, a lot of Pakistanis as well now… On top of that, since the University came, there is a lot more diversity. We have students coming from all over the world…often in transit…so Libyians, a couple of Saudia Arabians, some from Sudan…”

Cheltenham Synagogue:

“so we actually closed here for a long time, up until the war. Then, from the 1930s, the synagogue reopened for many evacuees, and also with the American soldiers who would come over, many were Jewish and would worship here”.

Language plays an important role in the transmission of tradition and religious practice. Ensuring transmission of knowledge to younger community members is also critical.

Hindu Temple:

“we have language classes here for the children [in Gujarati]. So every Friday, it is very important for our community, both for the religion but also for the survival of our culture”.

Migration can also lead to the evolution of religious institutions, as people with different cultural backgrounds and beliefs, converge on single centres of worship.

Cheltenham Mosque:

“There are cultural sensitivities, and then there are religious sensitivities. Islam itself is very diverse. There are so many cultures within our religion. So we come from one specific culture and we are used to certain ways of practising our religion, so when new people come along…the way they practice their religion can be different. It’s not a problem, but there can be some tension as people adjust”.

While places of worship might have thriving communities, this does not mean that community members will live close to one another.

Cheltenham Mosque:

“Cheltenham is quite unique…in that we don’t all live together in one place. We are quite spread out. Having said that, I think that’s not a bad thing because we’ve learnt to integrate into society quite normally”.

What is intangible heritage?

Heritage is a word with many different meanings to many different people. Intangible heritage is even more complicated. When we discuss intangible heritage, we are thinking about forms of ‘living’ heritage; customs, practices and traditions, things that only survive if people maintain them.

When migration happens, it is often intangible forms of heritage that travel with people. This could be the way people dance, cook, sing, worship, and much, much more.

The Diaspora project wanted to explore what forms of intangible heritage are maintained in Cheltenham from around the world, why it is important to people to keep these practices alive, and why some traditions are lost.

Below are a small number of the many examples we have identified so far. Other examples can be found throughout this exhibition.

Brazilian Intangible Heritage: the importance of food

“We in the south [of Brazil], prepare the best barbeques in the world. So I prepare how to cook and season the meat. Then I have most of the stuff in here [the store Made in Brazil] so we can still prepare those foods.

Here in the shop we have Brazilian street food, because in Brazil, every single day you are eating on the street. People come here just for that, because it reminds them of home!”

Chinese Intangible Heritage: martial arts

“For my grandparents, food was huge. It’s such a binding for everything. In Chinese culture, you don’t ask “how are you?”, you ask “have you eaten yet?”. My Grandfather opened the first Chinese restaurant [Ah Chow] in Cheltenham, so that is a legacy that he leaves behind”.

I remember watching my grandfather in the garden practicing Tai Chi. Now, Qigong is sort of the foundation for Tai Chi

‘My grandfather said to the whole family, that he wanted every single one of us to learn a martial art because, he said, at some point it could save their lives. I believe when he first moved to Cheltenham, he encountered a lot of prejudice because they were the only Chinese family at that time.

I went on to study Kung fu, and now I’ve gone back to Qigong and Tai Chi. It was my grandfather who inspired that, and it’s something I want to carry on, and bring to people in Cheltenham”.

French Intangible Heritage: the loss of tradition

“So Christmas, in France we celebrate Christmas on the 24th, 25th is hangover, and 26th is back to work. You celebrate it different, here it is all about the 25th. For the first few years, we definitely wanted to celebrate the French way, for a lot of reasons, habit being one…Then we realised we felt alone, because no one was doing that. After 15 years of being here, we decided to celebrate the English way, but because we do not have a big French community, maybe if we were more, we still might enjoy celebrating it on the 24th”.

Italian Intangible Heritage: Italian family traditions on the Lower High Street

“There was a strong emphasis on the importance of family, and marriage…almost an expectation as well on children, there were six brothers in the family after all..So marriage, work ethic, church, going to church and being part of the church family. Close links with the priests. I think as well, the desire for a strong standing in the community, that seemed to be very important in the Italian family”.

Jewish Intangible Heritage: The importance of transmission of information

“Here in the [Elm Street, Jewish] burial grounds, we still observe traditional burial practices, such as which side a person is buried on, family groupings, the style of, and type of text written on memorials. We also allow people to place small stones on graves when they visit, that is an important custom. But I’m the last one. After I go, for whatever reason, I don’t know if there will be anyone to keep up these traditions. Maybe they will just die out in Cheltenham when I die out? I don’t know if that is a bad thing, but I think it might well happen”.

Image courtesy of Dr Abigail Gardner.

Intangible heritage can be obvious, such as the practice and performance of martial arts, or much more subtle, such as when Christmas is celebrated, or the emphasis placed on religious institutions. Cultural tradition underpins all of these practices.

Do you have a migration story, where cultural traditions from that which was home, are still maintained in Cheltenham today?

We want to hear from you, and make a record of these traditions while they are still alive. It is very easy for these traditions to disappear, making it all the more important for historians to record them now.

Many students who spent time in Cheltenham went on to make big impacts. Of the earliest international students, perhaps few made as great an impact as Moses Craig Akinpelumi Adeyemi.

In the official college records for 1911, we found a reference to a student recorded as ‘M. C. Adeyemi, whose place of origin was only referred to as ‘West Africa.

The Diaspora team researched the name Adeyemi’ and identified it as a Yoruban name, which most likely came from Nigeria.

With help from the CRIMMS research centre in Lagos, we were able to build a picture of Adeyemi’s life.

Born in 1882, Adeyemi was a descendant of the royal Oyo family. Before coming to Cheltenham, he studied in the city of Oyo, in the south west of Nigeria.

Having received teacher training in Cheltenham, Adeyemi returned to Nigeria. Among many roles, he would go on to become the schools inspector for the Yoruba Mission area. From this position, he would go on to influence and shape education delivery for much of the region.

Adeyemi helped to establish the Ondo Boy’s High School, played a significant role in the establishment of the Women’s Training College and helped in the creation of the Ondo General Hospital.

Adeyemi was so well regarded in Nigeria, that the Adeyemi College of Education, opened in 1963, was named after him, in honour of his contributions to education in the region.

There is a statue celebrating the life of Adeyemi in the Royal Palace at Ondo.

We also found a reference to Elizabeth Modupeola Okuseinde. She studied at the Cheltenham School of Domestic Science, and would later marry Adeyemi in 1921.

We are still exploring Elizabeth’s story, and have learned that there are surviving members of the Adeyemi family, who we hope to make contact with in the future.

The Adeyemi story is of huge importance to the growth of education in Nigeria, and his time in Cheltenham would have been significant in developing the skills that he used to shape educational opportunities for generations to come.

Stories of migration are frequently associated with journeys of great difficulty.

Of all the stories shared with us so far, the journey of Czeslaw Maryszczak is one of the more remarkable. Today, Czeslaw Maryszczak is the chairman of the local Cheltenham branch, and the World Federation of the Polish Ex-Combatants Association. When he arrived in Gloucestershire, he was a teenager who had been driven from his home, and seen his family scattered across the world.

From Poland to Siberia

“I was born in Poland 1936, then at the age of 3 and a half, I was deported, and then I never lived in Poland again”.

“We were deported to Siberia, with mother, father, and my two brothers…we worked in forest cutting with very primitive conditions. People were huddled in one mud hut…You had to work for your food, in the forest. If you didn’t work, you would get your two slices of bread and whatever small amount else for your rations, if you didn’t work, you were dead”.

“I was too young to work, so I was sent to the play school, but the play school was mostly learning Russian songs praising Stalin”.

“My mother decided we had to leave now, otherwise we would be dead by winter. She had to bribe officials because it was illegal for us to travel in Russia. The conditions were very primitive and many died on the way to the Caspian Sea. My father left early, but he died in one of these train stations. Many died”.

Iran

“General Anders saw that the civilians were taken on ships. So we crossed the Caspian Sea, and eventually to Tehran (Iran), and lived under the tents. So we lived there for a few months, and said goodbye to my brothers, because they were to be trained. The mothers and the children were to be taken throughout the British Empire”.

Uganda

“We were taken to Uganda, to be away from the war. Where we were in Africa, there were many camps. Then we were in the jungle”.

“We were taken a place called Masindi on lorries. The first camp had a pump in the middle, and straw shacks around”.

“I was a bit older then, and I remember the mothers, who had very little luggage or anything after Russia, and I remember they all cried. After all the miserable time they had there and nearly died, and now they were in a jungle, with no lights, no nothing…from the lorries they could see what they were coming to and they all cried”.

“Then the next day the sun was shining… after so many months things started improving. The vegetation became clearer, so you didn’t have the snakes everywhere. You know eventually it was the best time of my childhood. I loved Africa. It was primitive, but after Russia we had food and safety”.

From Uganda to Cheltenham

Originally, post war, only wives and children of Polish men to have fought in the war were allowed to settle in the United Kingdom. Eventually, legislative changes were made to allow those whose sons had fought, which allowed Czeslaw and his mother to come to the United Kingdom.

“We went through India, because in the Indian Ocean, there were German u-boats in the way. So we waited six months in India before we could go”.

“August 1948, we landed in this country…then we went to Northwick Park in Gloucestershire. After two years in a Polish school, I came here with my mother. After I went to college here in Cheltenham, from then on, my town, my everything, was Cheltenham, the only place I can say is my home”.

“It is very sentimental because I never have a place to call my own. In Russia, it was mud huts, Tehran was tents, then it was mud huts in Africa, then came here and it was ex-army camps. Then when I came to Cheltenham, it was the first time I lived in proper houses”.

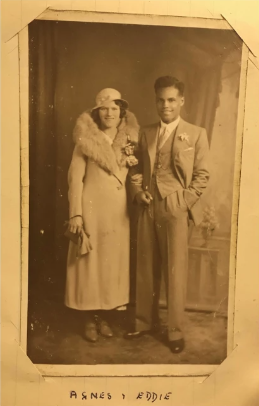

The time spent in Cheltenham by Eddie Parris was only brief, but his story is an important addition to the Diaspora project.

In 1931, Parris became the first black international footballer to represent Wales. He won a single cap playing against Ireland. While his career as a professional footballer stalled, his significance in Welsh sporting history cannot be disputed.

Parris came to Cheltenham Town after the war years, and played with the club in 1946. He would then move on to play and coach with Gloucester. Most of his family, however, remained in the area, including one of his descendants who went on to study history at the University of Gloucestershire, and contributed directly to this research project.

The Parris family, on Eddie’s fathers side, came from Barbados. John Edward Parris (Eddie’s father, though Eddie actually shared the same name) would go on to serve in the Royal Engineers in 1916. Before the first world war, in 1909, John married Annie Clarke. This interracial marriage would have been relatively rare at the time, and subject to significantly negative social responses.

The exact reasons for the Parris family moving to Gloucestershire are unclear. However, it has been suggested that the race riots which spread across Newport and Cardiff in 1919, might have forced the family to consider leaving the area.

When the second world war broke out, professional football largely ground to a halt. For Eddie, at the age of 28, it was to be the end of his professional playing career in the leagues. He would go on to work with the ‘Gloster Aircraft Company. During this period, Eddie went on to play for Cheltenham, and then in the region for the rest of his life.

The experiences of black people in and around Cheltenham, during the time of Eddie’s playing career, are poorly represented. Were it not for Eddie’s single cap for Wales, it is probably that his story would have been lost. Sport, however, offers a gateway through which we can access lost, or vulnerable historical narratives. Family archives are critical as well, and the project is indebted to Eddie’s family for their generous support in helping to tell his family’s story.

‘Parris, the coloured player at outside left, who was another personality of the match … It is surprising how often Parris has a hand in his side’s scoring efforts. Sometimes he may do surprisingly weak things; there were occasions in this game when he lost the ball without a Preston man near to take it from him. But one never knows when Parris may show a thrilling a burst of speed and either score or make the running for a goal”.

Leeds Mercury, 1934

We are always interested to hear the thoughts and responses of people who have been engaged in the exhibition, whether you were personally involved, visited the exhibition, or took the virtual tour online.

We would be grateful if you could spend a few minutes completing our survey.