| CC4HH

Three Murders on the Lower High Street

By Kayleigh Hather and Kevin McCloskey

Murder is an aspect of history that many people would prefer to ignore; it is dark history and a less popular story to be researched when making reference to a specific local area. This study focuses on three murders that all took place in the Lower High Street area in Cheltenham. Looking at this dark subject can reveal changes to societal attitudes and society as a whole. This study focuses on three case studies of murders and what they reveal about the changing demographics of Cheltenham, the increasing sensationalism of crime reporting, changing attitudes to the death penalty and how this is relevant in a heritage context.

The study draws much of its evidence from three murders in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The first is the murder of Katherine A’Court by her servant, Joseph Armstrong, in 1776. The second is the murder of Emily Gardner, who had her throat slit by her lover in 1871. Finally, Job Hartland murdered his wife and child in their family home in 1894.

The detection of these murders does not mean that the area around the Lower High Street was full of crime. In fact, the historical research carried out for this study found evidence of very few murders in this area. In the same way, the area has not become a centre of crime in recent times either. For example, in the first six months of 2017 in Cheltenham only 22 per cent of crimes were recorded as having been violent.[1] In March 2017 there were 102 violent or sexual offenses in Cheltenham, which is a small number in comparison to the area surrounding the UCL campus in London, where there were 420.[2]

The Crimes

Case 1: In 1776 William and Katherine A’Court came to Cheltenham to visit the baths. They were a respectable family: Captain William A’Court had a seat in Heytesbury in Wiltshire and they owned land there, including the Heytesbury Mill (see Figure 1). They were just two of a number of people who visited the town to drink the waters, including King George III who visited in 1788.[3] Cheltenham’s popularity soared in the eighteenth century with the population doubling from 1500 residents in 1700 to over 3000 in 1800.[4] It quickly became a fashionable place to be and as fashion so often came with wealth, so the people living here in the 1700s were often well respected gentry.

From the 1830s, however, the popularity of living in a spa town was decreasing and as the wealthy left, they were replaced by what may be considered as less respectable characters.[5] This fact provides one possible explanation for the changing demographics of the murders revealed by this study.

Case 2: In 1871 Emily Gardner was murdered in the street by her lover, Frederick Jones, who had become jealous of the time she spent with other men.[6] Emily, a dressmaker, lived with her parents above the Early Dawn Pub on the Lower High Street and Frederick was a baker who lived on nearby Swindon Place.[7]

Case 3: Job Hartland, a greengrocer, murdered his wife and child in an alcohol-fuelled attack in 1894.

Murder and Social Change

The difference in the social status of the people involved in the murders reflects a changing demographic, but does this seeming lowering in the social status of Cheltenham’s inhabitants provide a sufficient explanation for these incidents of violent crime? The simplest answer is no. Cheltenham was considered to be a respectable town in the 1700s but this did not stop Joseph Armstrong from killing his employer in an act of desperation. In fact, in the twenty-three years between Emily Gardner’s murder in 1871 and the murder of Hartland’s family in 1894, there appear to have been no other murders. This suggests that there were other changes taking place in society which influenced the decline in the number of murders. Cheltenham’s changing demographics did not lead to an increase in violent crime. This could be due, in part, to the establishment of the official police force after the introduction of Robert Peel’s Constabulary Act of 1839. (see Figure 2)

Media Reporting

Another prominent theme drawn from the research for these case studies was the increasing desire for sensationalised accounts of murder in the nineteenth century. This is reflected in a contemporary account of the murder of Katherine A’Court, written by an investigative officer on the case. (see Figure 3) The report presents much of the information seen in other contemporary accounts, such as newspaper articles from the period. Katherine had asked her husband to fire their servant, Joseph Armstrong, for misconduct and he had poisoned her with Arsenic to get revenge.[8] The A’Courts had not initially suspected Armstrong of attempting to murder his employer and had simply sent him away for his poor treatment of Katherine. This enabled him to flee as far as Frog Mill before being caught. It was not until a few days after her death that the apothecary reported that Armstrong had purchased Arsenic on both the day before Katherine was taken ill and again during the week before she died.[9]

In an 1863 publication on the history of Cheltenham, John Goding claimed that Armstrong had been caught stealing jewels and that he was prosecuted for theft as well as murder.[10] Contemporary accounts, however, do not include such claims, stating that Armstrong was only suspected of ‘neglect’ or ‘misconduct’.[11] The later sensationalised accounts of the murder also claim that Armstrong was caught because he was suspected of attempted murder by William A’Court, but as previously mentioned Armstrong was not suspected of this until several days after he had been dismissed. Goding’s history also claims that Armstrong took his master’s ‘favourite spaniel’ with him when he ran, and that it was the dog which gave him away when he was pursued.[12] These details are echoed in a 1922 report following the conviction of another Joseph Armstrong for murder.[13]

These changes in the details of the case indicate an increasing interest in stories of murder. People were keen to hear the gory and strange facts of a case, and this is reflected in the insertion of such details into the reports of later writers: Goding certainly had more interest in appealing to the excitement of his readers than in providing an accurate account of the murder.

The Punishments – Death Penalty

This section presents some of the evidence that demonstrates the changing social attitudes to the use of the death sentence and how these attitudes were reflected in the responses to three murders that took place in Cheltenham’s Lower High Street area between 1776 and 1894.

Case 1: After poisoning his mistress with arsenic in 1776 at their holiday home in Henrietta Street, Joseph Armstrong was sentenced to death following his trial at the Spring Assizes in 1777. One contemporary account suggests that having been detained at Cheltenham, Armstrong attempted to make good his escape, but was prevented from doing so ‘by the vigilance of the Constables’.

Armstrong, having then been convicted at the Assizes in the spring of 1777, took his own life rather than face the gallows in public. Armstrong’s body was then hung from a gibbet at the end of the Dunally Street at the junction with St Paul’s Road, a major coach road at the time. Was this hanging of the gibbet to serve as a deterrent to the local populous? Or was this something done with the approval of the local community, who saw the actions of Armstrong as abhorrent and that, having avoided the hangman, he had relinquished his entitlement to a Christian burial?

Case 2: The Early Dawn Public House was located at the corner of the High Street and Park Street and was home to the Gardner family. In 1871, Frederick Jones murdered Emily Gardner near Wellington Street, which, according to a report in the Cheltenham Chronicle on Saturday 8 September 1894, later became known locally as Murder Lane. Jones was detained very quickly by local police and was soon tried and sentenced to death.

Despite the brutality of the murder, Frederick Jones’s conviction to the death penalty was the subject of a petition seeking a reprieve. (see Figure 4) No evidence has come to light suggesting that the jury at his trial recommended him to mercy. Nonetheless, Jones was supported by a petition sent to the Home Secretary, Henry Bruce, but the petition was rejected. What can be noted on this petition are the signatures that reflect the support given by local people to Frederick Jones’s reprieve. In January 1872, Jones became the first person to be hanged behind the walls of Gloucester Prison, away from public view.

Source: National Archives, HO 45-9286-9315

Changing Attitudes from the Eighteenth to the Nineteenth Centuries

In less than 100 years, society had seen a shift from a public gibbeting of a convicted murderer to the private execution of another murderer behind prison walls.

Up to the end of the eighteenth century, executions were very much a spectator sport for all classes of society, the wealthy as well as the poor. In many counties, executions were held on market days to enable the largest number of people to see them and even groups of schoolchildren would be made to attend as a moral lesson. The efforts to reduce the number of capital crimes, and thus executions, that had been evident from the end of the eighteenth century and during the first 40 years of the nineteenth century had met with considerable success, yet between 1828 and 1833, the number of executions still averaged over one a week in England and Wales; between 1850 and 1868 there were 215 public executions.[14]

Although there was apparently little mood in the country for the outright abolition of capital punishment, it seemed that watching public executions had become unfashionable, at least with the upper middle classes. The Criminal Law Consolidation Act of 1861 reduced the number of capital crimes to four: murder, high treason, piracy and arson in a Royal Dockyard. In reality, this act was more of a tidying up exercise as nobody had been hanged for a crime other than for murder since 1837. The 1864 Royal Commission on Capital Punishment, however, concluded that there was no case for the abolition of the death penalty, but it did recommend putting a stop to public executions. In 1868, England and Scotland carried out their last public executions, and in Wales the last public execution took place in 1866. On 29 May 1868, the Capital Punishment (Amendment) Act came into force ending public hanging, and requiring all future executions to be carried out within prisons.[15] Between 1792 and 1864, 102 prisoners were hanged in public in Gloucester jail: 94 men and eight women. The last public execution at Gloucester was carried out on the 27 August 1864.[16]

Changing Attitudes in the Late Nineteenth Century

Case 3: In 1894, Job Hartland committed the heinous crime of murdering his wife and baby son at 303 High Street, on the corner with St Georges Street. Despite the brutality of his crimes, Hartland was the subject of a petition signed by influential businessmen and clergy from Gloucester. Furthermore, he had the support not only of the jury at his trial, but also of the Judge (see Figures 5 and 6).

No evidence has been found to suggest that Frederick Jones had been the beneficiary of similar attitudes 23 years earlier, in 1871. Was the reason for Jones’s failure to obtain a reprieve more about his lack of influence rather than the stronger social acceptance for capital punishment? Even so, despite the petition in his support, Job Hartland’s reprieve was met with some surprise amongst the Cheltenham community, as evidenced in local newspaper reports.[17] (see Figure 7) This may be a sign that attitudes had not changed quite as dramatically locally in Cheltenham as across the Golden Valley in Gloucester.

Source: Gloucester Journal, Saturday 8 December 1894

Reporting the Murders

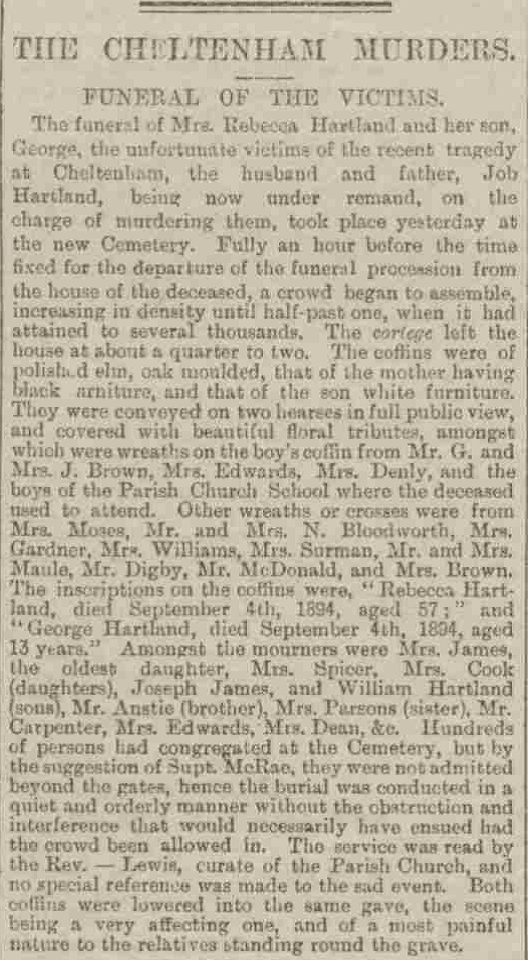

Despite the rising number of murders recorded nationally, the incidence of murder in the Cheltenham Lower High Street area attracted public comment simply because it was not common. The numbers of people attending the funerals of Mrs Hartland and her son became so high that the Police had to deny access to anyone other than family rather than turn the event into a public spectacle. On 8 September 1894, an article in the Gloucester Citizen made reference to the ‘Several Thousands’ who had assembled on the High Street. (see Figure 8)

Source: Gloucester Citizen, 8 September 1894

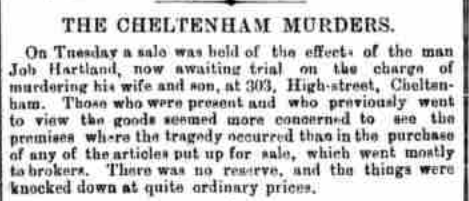

Detailed accounts of the crimes of murder became increasingly common and can be linked more generally to an ever increasing interest in the macabre. The Gloucestershire Chronicle on 29 September 1894 reported behaviour which would suggest that the interest in the macabre was as evident then as it is today. (see Figure 9)

Source: Gloucestershire Chronicle, 29 September 1894

Lower High Street Heritage

The present day popularity of ghost tours, haunted house TV shows, films and books about killers suggests that there is a possible space in Cheltenham heritage to explore this narrative. The three case studies of local murders examined here present an opportunity to see and feel history up close:

- The house in Henrietta Street where Mrs A’Court was poisoned;

- Dunally Street junction with St Pauls Road;

- St Marys Church, where Katherine A’Court is buried (a plaque commemorates her memory);

- The Shamrock Pub (previously the Shakespeare Pub) where the inquest was held for Emily Gardner;

- The Early Dawn Public House, no longer a pub but the building still stands at the junction of Park Street and the High Street;

- Wellesley Street (Murder Lane), where the murder of Emily Gardner took place;

- Gloucester Shire Hall and County gaol (soon to be closed), where Armstrong, Jones and Hartland were convicted and spent time. Jones himself is buried within the walls of Gloucester Prison;

- 303 High Street, the scene of the murders of Rebecca Hartland and George Hartland;

- New Cemetery, where the victims are buried.

Cheltenham’s Lower High Street area was the scene of the three murders detailed here in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. These types of murder were mirrored around the country and the Lower High Street was in no way unique. Although the demography of Cheltenham changed considerably during these centuries, there was no significant increase in the local incidence of murder. There was, however, an increase in the public appetite for sensationalism in the nineteenth century, leading to a more detailed and widespread reporting of crime. Changes in the law resulted in executions taking place in private and this reflected a social change in attitudes towards capital punishment. As the nineteenth century neared its end, the attitude to capital punishment was reflected further in the granting of conditional pardons.

References

[1] UK Crime Stats, http://www.ukcrimestats.com/Constituency/65946 Copyright UK Crime Stats 2011 (accessed 19.06.17)

[2] Crime Statistics.co.uk, https://crime-statistics.co.uk/compare/postcodes/GL51%209NJ+WC1E%206BT Copyright Crime Statistics, 2017 (accessed 19.06.17)

[3] Cheltonia, https://cheltonia.wordpress.com/spa-town/ (accessed 19.06.17)

[4] Cheltonia, https://cheltonia.wordpress.com/spa-town/ (accessed 19.06.17)

[5] Cheltonia, https://cheltonia.wordpress.com/spa-town/ (accessed 19.06.17)

[6] Sheffield and Rotherham Independent, 9 January 1872.

[7] Birmingham Daily Post, 23 December 1871.

[8] Swindon and Wiltshire History Centre, WSHC 635/152.

[9] ‘Monday’s Post’, Country News, Monday 30 September 1776.

[10] John Goding, Norman’s History of Cheltenham (1863), p. 179.

[11] The Newgate Calendar, (1780), The Gloucester Journal, (17 May 1777)

[12] Goding, Norman’s History of Cheltenham, p.180.

[13] Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic, ‘Another Armstrong Murder’, 3 June 1922.

[14] http://www.capitalpunishmentuk.org/endpublic.html (accessed 9 June 2017)

[15] http://www.capitalpunishmentuk.org/endpublic.html

[16] http://www.capitalpunishmentuk.org/endpublic.html

[17] See also Cheltenham Chronicle, Saturday 8 December 1894.